Worthing gets television

THOSE living in 1931 witnessed events that were exciting, traumatic, disastrous and prophetic. Much like any other year you could say.

It was the year the Road Traffic Act came into force, introducing traffic policemen and compulsory third party insurance. The year that Malcolm Campbell broke the world speed record at 245mph, the Empire State Building in New York became the world’s tallest building and women condemned the return of the long skirt as an infringement of their liberties and comfort.

That year, too, Britain was in the throes of its worst-ever financial crisis, was forced off the gold standard and had to devalue the pound. In America, death-dealing gangster Al Capone was finally jailed (for tax evasion) while in Germany Hitler’s Nazis were winning their first state election.

Here on the South Coast we experienced the arrival of a little-known invention that a handful of people with more foresight than most were hailing as “the eighth wonder of the world.”

TODAY, television is a totally integrated part of everyday life. It is easy to forget there ever was a time when the merest flicker of movement on the tiniest of television screens (let alone a full screen picture) would excite exclamations of disbelief.

If you were asked when the first television pictures were received in this part of West Sussex you might hazard a guess that it was 30 or perhaps even 40 years ago. In fact, as early as 1931 television had passed the experimental stage and was an accomplished fact. In London and the North radio amateurs had taken it up with great enthusiasm though little headway was being made here in the south.

In January that year Edgar Lamb, who had been studying broadcast vision for several years, decided to install Worthing’s first fully working television receiver at his home in Durrington.

His decision made local newspaper headlines and gasps of amazement greeted the unveiling as his TV set with a tiny six-inch screen flickered into life to show the semblance of a moving picture. Onlookers were reported to be “much impressed by the excellent results obtained.”

How different the reactions were compared with today’s casual acceptance of huge, brilliant and totally sharp flat-screen TV pictures.

One man who watched that first television programme to be received in Worthing on Edgar Lamb’s miniscule screen in 1931 said of the programme, “A comedienne was being transmitted. The likeness was exceedingly good and we had no difficulty following every change of expression and each movement of the hands.

“One could even see the light reflected from the hair….

“The announcer who followed the programme was very clear and the screen news bulletin at the end giving details of the next day’s programme could be easily read.”

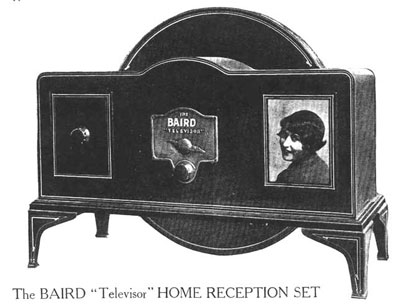

Those earliest regular television programmes came from John Logie Baird’s studios in Long Acre, London, over Baird’s own relatively low-cost 30-line picture system.

Four photoelectric cells (then commonly known as “electric eyes”) were placed above the televised artist, who was seated.

An electric lamp shone through an aperture in the wall onto the performer and between the lamp and the aperture was a perforated disc revolving at the rate of 750 revolutions a minute.

The ordinary microphone for broadcasting song and speech was hung just to the left of the artist.

Light shining through the revolving disc on to the person set up a variation in the current of the” electric eyes.” These were amplified and passed on to the transmitter in Brookman’s Park

The ordinary radio listener who tuned their set to 356.3 metres during the hours of television then heard “a sort of hum” in the loudspeaker caused by the variations through the “electric eyes.”

Those possessing television sets then switched over to the televison and this transformed the “hum” back into a pictorial representation of what was happening at Long Acre.

On the receiving end two knobs controlled a revolving disc similar to that at the transmitting station and the whole set.

The first knob adjusted the speed of the receiving motor driving the disc to approximately that of the transmitting motor.

The second worked electromagnets that held the picture in the middle of the screen and prevented it from wobbling.

“The whole thing,” noted one looker-in (as viewers were then called) “is simpler than handling many wireless receiving sets.”

Unfortunately for Edgar Lamb, the BBC, after initially adopting John Logie Baird’s 30-line television, abandoned it in 1936 in favour of a competitor’s much higher definition, fully electronic 425-line transmission system.

Worthing’s first television set, together with a few hundred other Baird sets mostly in London, became redundant overnight.