Shelley family and Horatio Smith

PERCY Bysshe Shelley, one of the finest lyric poets in the English language and with strong family connections in Worthing, wrote about a friend, “Is it not odd that the only truly generous person I ever knew who had money enough to be generous with should be a stockbroker? He writes poetry and pastoral dramas and yet knows how to make money, and does make it, and is still generous.”

Shelley was referring to Horatio Smith, a stockbroker in the City who, unusually, combined his day job making a lot of money with being a poet and novelist. While it was Princess Amelia, youngest daughter of George 111, with her more glamorous background, who gathered most of the credit for starting the rush to this particular part of the South Coast two decades earlier, Horatio Smith was probably equally responsible for Worthing’s growth as a seaside resort. He did much for Worthing in a single humorous article published in a London magazine but failed to write much else that history remembers.

On the occasions that Horatio Smith put quill to paper, he mostly recorded matters of a light humorous nature. How sad he would be today to discover that his period pieces are all but forgotten, his puns and witticisms failing to stand the test of time.

His playwright friend, Richard Cumberland, first told him about Worthing in 1822, when it was still a tiny, insignificant town, hardly known to most residents of the capital.

Out of obligation to his friend, Smith visited Worthing in September that year and his descriptive notes, published in the New Monthly Magazine before the year was out, in the character of a Cockney grocer of Tooley Street, who had spent seven days in Worthing, unsuccessfully trying to penetrate the fashionable society of the town.

was not great literature but its humorous content was long remembered by the magazine’s readers. It also encapsulated for history a unique “snapshot” of Worthing as it was in 1822.

Just how highly Horatio Smith regarded the Worthing of 1822, I’ll leave you to judge from the following extracts.

Monday Sept 2 1822: Set off from Tooley Street in Newman’s patent safety-coach, for Worthing. Stopped at Elephant and Castle. Drew up cheek by jowl with Tom Turpentine, who was outside the Brighton Comet (a rival coach). Asked me why I went to Worthing: told him how select the society was. Tom grinned and betted me a bottle that I should be at Brighton before seven days were over my head.

Bought three pears at Dorking: offered one to gentleman in front, which he declined and took a paper of sandwiches from his pocket. Never offered me one, which I thought rude.

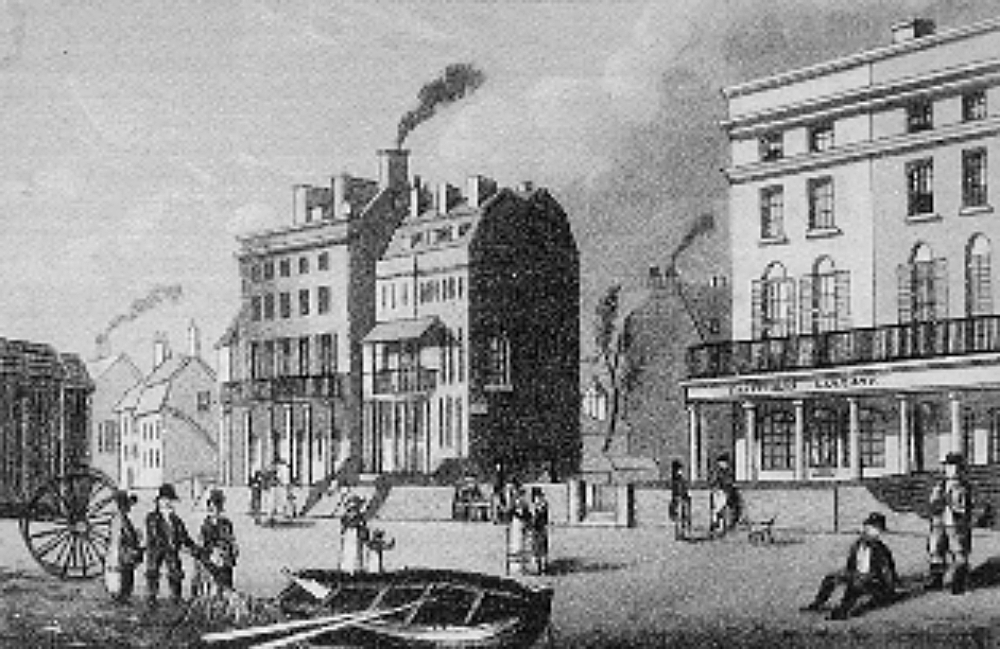

Arrived at Worthing at half past four. Head dizzy with the rattling of coach steps. At the Steyne Hotel ordered a veal cutlet at five and walked out to view the ocean. Never saw it before and never more disappointed. Expected waves mountains high, shrieking mariners and swamped longboat but it was as smooth as West India docks.

Walked up to Wicks’s warm baths upon the Pebbles – natives call it the Shingle.

Opened window of coffee-room to get health enough for my money. Ann Street Theatre playbill for “Cure for the Heart-ache” advised performance to begin at seven.

Took a stroll five times up and down Ann Street to pass the time. Saw two ladies alight from a coach that had no legs. Asked the driver what it meant; told me it was a fly. Looked more

Tuesday. Prawns for breakfast: like shrimps better. Looked through a telescope. Bathing machines marked “for gentlemen only”. Oil painting in coffee-room of woman riding on dolphin’s back, without a rag covering, and black-bearded man floundering and blowing a trumpet beside her.

Machines “for gentlemen only” and ladies obliged to do without. Bathing at Worthing not so select as society..

Walked to Stafford’s Library, paid seven and -sixpence and put down my name in a book. Looked over list of visitors: Earl of Elderbury; Lady Seraphina Surf; General Culverin; Lord and Lady Longshore; and Sir Barnaby Billow. Rubbed my hands and thought we should make a nice snug party.

Dined upon fried soles – tasted too much of the sea. Walked out to view the town; every shopkeeper named either Wicks or Stubbs. Library in the evening: dull and cold. Girl in pink played “We’re a’Noddin,” and sure enough we all were.

Wednesday. Heard a nursemaid, under coffee-room window, say the tide was coming in. Despatched breakfast in haste, fearing I should be too late. Ran down the beach…little though there was any danger till a wave rose above my shoes.

Dined on veal pie. Sir Barnaby Billow came into the room to look at a map of the county. Told him it was a very fine day to which he replied “Very”, pulled the bell and walked out of the room.

Wondered when I should be one of the select society and said to myself “Phooo! He is only a baronet.” Telescope again: cast a longing look towards Brighton.

Play at theatre was “Honey Moon” with Miss Dance from Brighton. Too lady-like; looked above her business.

Walked to beach and stood for half an hour to see a lighter discharge coals by candle-light; smacked my lips and felt as if I had been eating salt. Went to bed and dreampt (sic) of Miss Dance.

Thursday. Swore an oath that I would go into the sea and got into a machine to avoid being indicted for perjury. Began to undress and in one minute the machine began to move. I wondered where I was going. Fancied it was at least half a mile. Was upon the point of calling for help, when the driver turned about.

Stood trembling on the brink and at last jumped in: just time enough to be too late. Hit my elbow against the steps and lost a ribbed cotton stocking. Felt quite in a glow and went home in high spirits to get another stocking. Elbow painful. Little finger asleep.

Donkey cart to Chanctonbury Ring. Driver said finest prospect in the world. Asked him how much of the world he had seen? Answered, “Lancing, Shoreham and Broadwater Green.” Donkey jibbed at foot of hill. Got out and dragged him up by left ear. Paid driver three and sixpence and said nothing about it.

Dined upon cold beef, went to Library. Girl with a harp; all nodding again. Opened “The Fortunes of Nigel” and found my nose flat upon the third page before I knew where I was.

Friday. Low water – all the world promenading on the sands. Lady Seraphina and the General on horseback. Patted her Ladyship’s poodle-dog and cried “What a beauty”. Lady and General off in a canter and poodle followed, barking. Thought select society rather rude and began to doubt whether a touch of vulgarity would not make it more polite. Sand dry as a bone, began to be as dabby as a batter-pudding. Made for the shore and found myself quickly surrounded by water. Saw a boy making a bridge of stones; passed over and gave him a penny. Lad grumbled; told him I paid no more to cross Waterloo Bridge, which cost a matter of a million of money.

Strolled up Steyne-row into the town. Stopped at the corner of Warwick-street and looked into a grocer’s shop. Took a walk on the Lancing-road. Met some gipsies, who told my fortune. Said I should be in a great place shortly. Told them I hoped I should.

Saturday. Market day. Spent two hours in seeing the women spread their crockery on the pavement. Bought a bunch of grapes and stood under the portico of the theatre, spitting the skins into the kennel.

Saw the Earl of Elderbury and Sir Barnaby Billow in a barouche. Lady Seraphina again on horseback.

Went up to my bedroom, yawned five times and fell asleep. Awakened by waiter with candles. Read the Brighton Herald right through, including all its fashionable arrivals and wished I was there. Poured over map of Sussex. Counted the knobs on the fender. Read half through the Army List on the mantelpiece, thrust my feet into a pair of slippers without heels and went to bed.

Sunday. Chapel of Ease (later renamed St Paul’s Church). Sermon for the benefit of two free schools. Plates held by Lady Seraphina and Earl of Elderbury. Happened to go out at Lady Seraphina’s door. Meant to give only a shilling but plate being held by a dame of quality, could not give less than half a crown. Never so much as said “Thank-ye”. Select society quite out of my books.

Strolled as far as Broadwater-common. Aided by a crooked stick, amused myself by picking blackberries. Broke off a fine branch laden with fruit and bore home my prize in triumph, and gave it to a child at the corner of South-street. Evening pretty much like the last.

Monday. Remounted Newman’s patent safety. Never so happy. Seriously ill at starting but better as I approached wholesome London air. Sniffed the breezes of Bermondsey with peculiar satisfaction and reached Tooley-street just in time to despatch the following letter to Tom Turpentine. “Dear Tom – No more weeks at Worthing! Select society is all very well for select people. Yours to command.”