The case for the defence

IT’S characteristic of the British. Order us to do something and we often respond grudgingly and sluggishly. But ask for 150,000 volunteers in a good cause and more than 250,000 men will turn up the very next day!

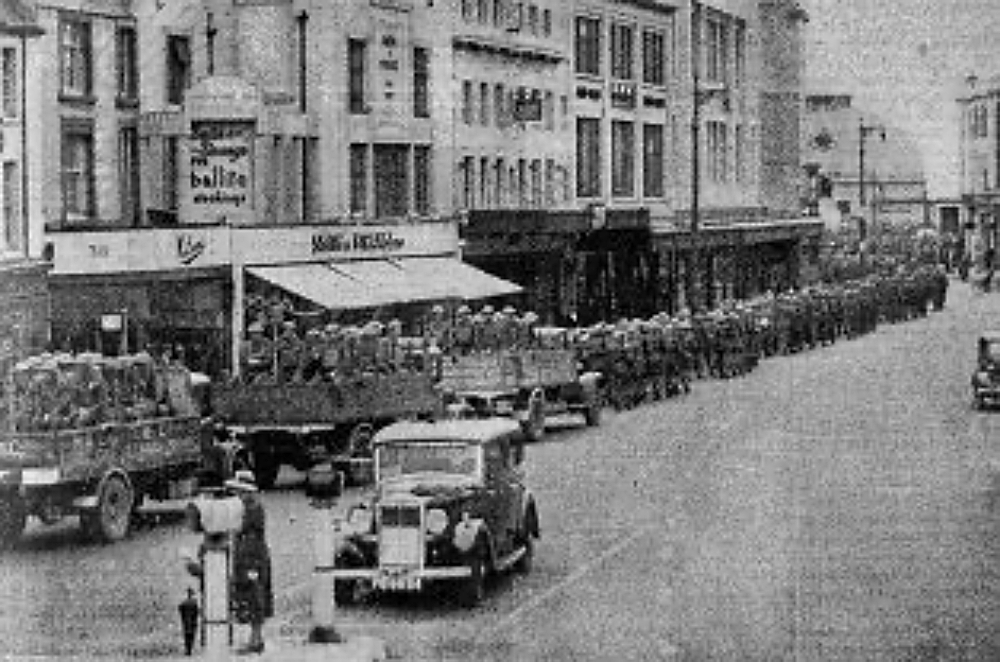

hat’s exactly what happened in May, 1940, when Britain’s wartime leader, Winston Churchill, told the people of Britain: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat,” and Secretary of War, Anthony Eden, announced the formation of the Local Defence Volunteers. The call went out for volunteers between the ages of 17 and 65 who were too young, too old or insufficiently fit for the army, navy or air force. And being a member of the LDV would not be a full-time job. “You will not be paid,” warned Mr Eden, “but you will receive a uniform and be armed. You will form part of the Armed Forces but will not have to move away from home.”

NO sooner had Eden finished his speech on the BBC than volunteers jammed police station telephones all over Sussex.

Next day, the first LDV patrols set out to scour the Downs behind Worthing for the expected German parachutists and spies.

People on the home front were just getting used to watery wartime beer, pubs being crowded and glasses in short supply. You often had to pounce on an empty glass and hand it back at the bar before you could get served with half-a-pint of bitter.

Holland and Belgium had been over-run and France was on the brink of collapse. Everybody was convinced that Hitler’s hordes would soon follow-up these victories with the invasion of Britain.

Most men considered to be of fighting age had already been called into the armed forces.

Those still at home were either too young, too old, or in reserved occupations vital to the war effort.

Those who volunteered for the LDV soon discovered they were expected to meet an invasion by crack German troops with little more than a collection of old shotguns and pieces of gas pipe with bayonets welded to the end.

This was the moment when, if there had ever been any doubt, most people realised the defence of Britain had became a matter of life or death. Within a month, the strength of the LDV climbed to well over a million men from every walk of life. Even ageing ex-brigadier-generals like the Hon Alexander Victor Frederick Villiers Russell CMG MVO, a godson of Queen Victoria, signed up.

They were a motley lot but providing they could claim to be “physically active”, they could join.

But they must be British, not a member of the clergy, and most definitely not a woman.

The ban on women joining was eventually lifted two years later and several members of the clergy signed up regardless, insisting it was their right to enrol “to help defend their hearth and home and those of their neighbours”.

Boys of 15 pretended to be nearly 17 so they could become LDV messengers and runners.

Comedians of the day quickly christened the LDV the “Last Ditch Adventure” or the “Look, Duck and Vanish Brigade”.

As one of the most important factors in forming the force was to boost civilian morale, it was hardly surprising that only three months after its formation, the name was changed from LDV to the Home Guard!

Biggest problem for the Home Guard was still the shortage of effective weapons, so many having been abandoned on French beaches when our troops were evacuated from Dunkirk.

Public appeals produced a sparse and mixed array of weapons. For much of 1940, for example, the East Preston platoon of the Home Guard boasted just one shotgun for the entire unit.

Another local unit was equipped with a single rifle and an otter pole (don’t ask!) passed from man to man as each took his turn on sentry duty.

Best known of the home-made weapons issued to the Home Guard in its early days was the Molotov cocktail. Basically, it was a bottle and preferably a wine bottle, because the longer stem made an excellent handle for throwing.

It was filled with a concoction of petrol, oil and creosote and sealed to prevent evaporation. With a strip of rag for a fuse, the lethal cocktail would hopefully explode on being smashed against the side of an enemy tank.

Many weeks later, Worthing’s Home Guard units graduated to the occasional Thompson sub-machine gun, Mills bombs and real hand grenades.

Because Worthing was geographically close to the centre of Britain’s first line of anti-invasion defence, the town’s Home Guard had to respond to several invasion alarms during 1940.

The commander of the Home Guard Goring section was awakened at 4.30 one June morning by a message that unidentified ships were approaching the coast. Fortunately, they did not turn out to be German invasion barges but ships carrying Allied troops being evacuated from Cherbourg.

It was on September 7, that the dreaded codeword “Cromwell” was issued and the entire Home Guards turned out at the double. It was the warning everybody had been waiting for, signalling that conditions were “most suitable” for a German invasion attempt, which could, therefore, be expected at any moment.

Thanks in part to the Battle of Britain, at that moment being fought in the skies above the Home Guard’s sandbags, roadblocks and thinly strung-out gun emplacements, the invasion never came. Hitler changed his mind at the 11th hour to turn his attention towards Russia.

On May 20, 1941, to mark their first anniversary the Home Guard was given the task of mounting guard at Buckingham Palace – a morale-boosting exercise at a critical time.

Although, in real life, the Home Guard was rarely as funny as was portrayed in the post-war “Dad’s Army” television series, people who lived in Worthing during the war still recall some amusing incidents.

Mrs June Spells is one. Her mother, hearing a strange noise at the rear of her house in east Worthing on a moonless night in 1940, uttered a challenging if rather reckless “Who’s there?”

Two men loomed out of the darkness, crawling on their stomachs along her rear garden passageway. “Shush!” they hissed. “Go back indoors.”

In hushed tones, they explained they were scouring the area following an alert that German troops were “expected on our beaches at any moment”. As they were wearing Home Guard uniform, the disturbed woman went back to bed, reassured that her safety was in good hands.

When women were finally allowed to penetrate this all-male preserve in April, 1943, 132 of them joined the Worthing battalion. They were never allowed to wear the Home Guard uniform but had to make the best of a badge with the letters HG circled by laurel leaves.

The Home Guard distinguished themselves in many fields of bravery – during air raids, in the disposal of unexploded bombs, when things went wrong during hand grenade practice, rescuing people from crashed planes and in ground-based action against enemy aircraft.

Two members of the Home Guard won the George Cross – the highest distinction they could be awarded for bravery – 13 the George Medal, 12 the MBE, 49 the BEM, one the Military Medal and 59 received the King’s Commendation for Brave Conduct. Four of the awards were made posthumously.

The Home Guard officially “stood down” in December, 1944, and was disbanded one year later.