Man shot in Salvation Army riots 1884

THE year was 1884 and an increasing number of holidaymakers were visiting Worthing on a regular basis. New landmarks in the town included elegant kiosks on the Pier and a large roller skating rink on the east side of Montague Place. A new hospital had opened in Lyndhurst Road and close-by increasing leisure time was being catered for by the new 14-acre Homefield Park with its attractive lake. New churches seemed to be opening every few months. But the Worthing Gazette, in its second year of publication, would soon be reporting on events that threatened to spoil it all….

IN 1884 (even in “peaceful, quiet and elegant” Worthing) if a prominent citizen offended the proletariat it was not unusual for an effigy of him (or her) to be burnt. And that year, a nucleus for disorder was never dormant.

So when on February 23, 1884, some of town’s rowdies shouted rude names in the middle of a meeting of the newly formed Salvation Army, nobody was greatly surprised. For the Salvationists had announced their intention of seeking just such lost souls as these to save.

Unfortunately, the interruptions caused the meeting to be abandoned and some of the noisiest elements were summoned to appear in Worthing Magistrates Court next morning. What followed gained Worthing a period of notoriety that lingered for decades.

The crisis peaked at 4.14 on Sunday afternoon, September 7, 1884. Not a time or date many people will immediately recognise as significant. But that bloody Sunday was the baptism by fire for the organisation many have since come to fondly know as the Sally Ann.

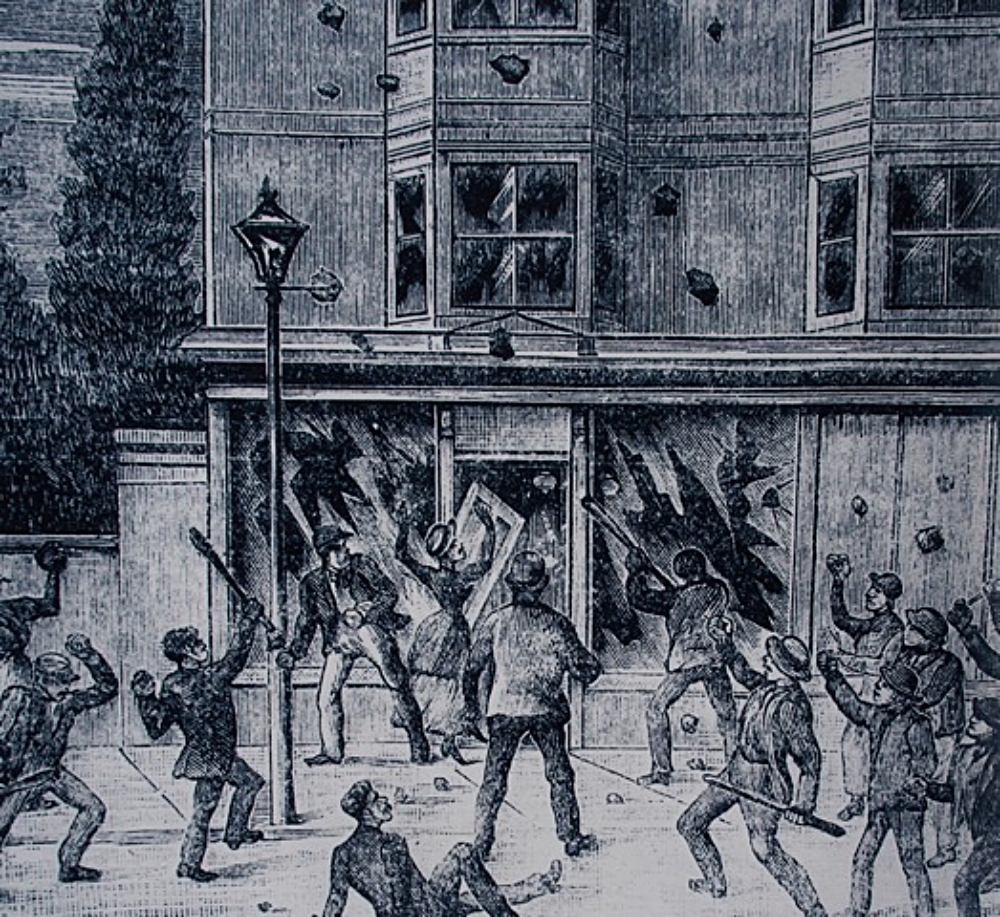

A mob of nearly a thousand yelling, shrieking men, women and boys were attacking the shop and home of Mr George Head, painter and plumber, in Montague Street, Worthing. They had already smashed every pane of glass in the building when suddenly a shot rang out.

Then two more shots.

The effect was electrifying. As the mob stopped in its tracks, cab driver Edward Olliver fell to the ground with blood spurting from his neck.

But let us return to when the seed for all this fury and anger was sown by those “noisy elements” arrested for their noisy behaviour the previous February. On the day following their court appearance the Salvation Army held another public meeting. More interruptions ensued, followed by further prosecutions.

It might have all ended there, had the Salvation Army agreed to hold all further meetings indoors. But under their new captain, 23-year-old Ada Smith, they declined. She insisted on their right in law to march through the streets of Worthing twice each Sunday, singing their unfamiliar and lively hymns and prominently displaying their banner.

This was inscribed `Blood and Fire 458′, the regimental number of the Worthing detachment.

On Easter Monday April 14, 1884, as the Salvation Army band of two cornets, a shiny new triangle and a very big drum, led a procession through the streets, physical violence was used against them for the first time.

Edward Standing was arrested and fined £2 for assaulting a Salvationist.

It was the spark that set off a systematic campaign against the religious newcomers, who were preaching against “ the demon drink.”

It didn’t take much persuasion for the troublemakers to enlist financial support for their campaign from the keepers of some local beer houses who felt their businesses were being threatened by the Salvation Army’s main objective.

Even some of the “more respectable” trades people of the town joined in the protests because they saw the Salvationist processions as a disturbance of their quiet Sunday afternoon. They also feared the noise might frighten away the free-spending holidaymakers who were just beginning to enjoy the habit of an annual visit to `one of the quietest, most respectable little towns on the South Coast.’

Little did they realise how much terror and violence their acceptance of the escalating situation was about to unleash.

Fast forward to early July the same year, when shoppers in Worthing’s Chapel Road were startled to be confronted by a rowdy group of marching men carrying a black banner daubed with a hideous white skeleton.

The marchers turned out to be opponents of the Salvation Army who had decided to actively resist Salvationist pleas for them to “turn away from the demon drink and save their souls.”

As the marchers approached the Town Hall in South Street, several police constables ran out from the county police station, just around the corner in Ann Street, and seized the banner and its two bearers. The two men were hauled before the magistrates and fined for obstruction.

Early the following Sunday morning, a small party of the Salvation Army in their distinctive scarlet uniforms paraded unhindered through the streets of Worthing singing hymns. But when a second procession set out at 10am, the Skeleton Army staged a noisy counter demonstration, this time carrying three skeleton banners.

Police attempted to stop the Skeleton Army and seize their banners but the singing, whistling, shouting mob stoned the constables and hit out at them with sticks.

Similar parades were held that evening but this time the police stayed away.

On the following two evenings the Skeleton Army repeated their march through the town, so by Wednesday, members of the public were only too anxious to attend a public meeting at the Montague Hall, hoping it might resolve the disquieting situation.

Instead, the meeting turned into an attempt by Skeleton Army leaders to force owners of the Montague Hall to refuse the Salvation Army use of the building for their gatherings.

Some under-estimated the danger signs.

There’s little doubt that the majority of townspeople believed all the trouble would cease if only the Salvation Army would stop parading through the streets but it was another matter when two of the town’s magistrates in open court on July 14 verbally attacked the Salvationists.

George Marner, Salvationist, was applying to the court for a summons against members of the Skeleton Army for assaulting him and tearing down a Salvation Army banner on the previous Sunday morning.

Magistrate Mr E. Henty turned on Mr Marner and accused him of “provoking a disturbance. To which another magistrate, Mr W.F. Tribe, added, “The Salvation Army processions are a disgrace to you and the town. You know that what you do provokes others to interfere with you and then you come to us for protection.’

Interjected Mr Henty: `It is a desecration of the Sabbath and you provoke all this riotous behaviour.’

Perhaps this antagonistic outburst by the two magistrates was responsible for a month of comparative silence from both sides. During this period the Salvation Army did not parade in the streets and many concluded that the magistrates had correctly, if not fairly, placed the blame.

But a bomb exploding in a hospital full of children could not have unleashed more hatred, mob rioting and violence than was experienced in Worthing during the week beginning August 17, 1884.

After a month to lick their wounds, detachment 458 of the Salvation Army marched on that Sunday through Montague Street via Crescent Road, Clifton Road, Teville Road and Chapel Road to South Street. A Skeleton Army procession immediately formed up and marched directly in front of them.

Parodied songs drowned hymns as the Skeletons slowed their pace until they were treading on the toes of the leading Salvationists. On reaching Bath Place, the Skeleton Army followers suddenly ran ahead, turned about and charged the Salvationists.

Police rushed in to protect the attacked. Policemen lost their helmets `and were kicked and struck with great violence.’ The assailants then turned their attention to the Salvation Army barracks around the corner, where as they hurled rocks through the windows, Salvationists who had been praying dived under seats for cover.

The mob’s violence was now directed against Mr George Head, a painter and decorator with a small business in Montague Street, who had rented a storehouse in Prospect Place to the Salvation Army for use as its barracks. Not long after he had converted to the rank and file of Salvation Army followers.

Soon after eight o’clock the next evening, hundreds of shouting and jeering people rained a hail of missiles on George Head’s shop and home and, with every window in the place broken, eight men kicked in the shop door.

George Head confronted them, flanked by his two sons aged 22 and 16, one wielding a shovel, the younger one a pitchfork. Shovels swung and heads were clouted. All the lights went out. Three times the mob retreated then returned.

Windows, clocks, shades, pictures, frames, a piano and even a picture of the Crucifixion in the drawing room were stoned. Having smashed up much of the house and its contents the maddened intruders surged forward in a fourth attack.

This time George Head threatened to fire a revolver in defence of his family and home but the warning had no effect.

He fired six times, the final shot being aimed at Edwin Eldridge, who with Arthur Reed was striking matches under the shop counter, in a deliberate attempt to set the building on fire.

George Head’s youngest son took the revolver to reload, but it proved defective and exploded in his hand, the cartridge lodging in his wrist.

A thousand people now thronged Montague Street. Mob rule seemed inevitable but not a single policeman appeared on the scene.

The senior police officer on duty that traumatic day was later to tell an inquiry that the eight policemen manning the Ann Street police station already had four prisoners in their charge when the call came for help. He had decided that if some of the constables were sent to try to quell the mob attacking George Head’s home, the assailants would probably have turned on the police station and freed the prisoners.

What happened the next day, August 20, 1884, proved to be the most infamous day in Worthing’s history and it was reported all around the globe.

It began quietly enough when, at the magistrate’s court held in the Old Town Hall, 15 men were fined nominal sums for causing obstruction in the streets. The magistrates were tougher with six men convicted of assaulting the police. They were all given jail sentences.

Crowds began gathering outside the Town Hall and police station a few yards away. Somebody shouted that the police would never be able to transfer their prisoners to jail because the Skeleton Army wouldn’t let them.

By late afternoon, between 3,000 and 4,000 people thronged South Street and as darkness fell the crowd became even more excited and defiant.

A call for volunteer special constables had gone almost unheeded, so the magistrates summoned 16 local businessmen, swore them in as `specials’ and gave them white armbands to wear.

By this time, hails of stones flung at the police station had smashed every window in the building.

As rumours spread that homes of magistrates would be next on the target list, a strong guard was posted around Broadwater Manor, home of magistrate W.F. Tribe.

When at last the tardy arm of law and order did spring into action, it did so swiftly.

Lieutenant-Colonel Wisden, chairman of the magistrates, decided the police on their own were powerless to deal with the ugly situation, so just after 8pm he sent a messenger to Preston Barracks in Brighton, urgently requesting the assistance of the Army.

By 11pm a dusty, a perspiring column of 39 men and three officers of the Royal Irish Dragoons were clattering along Warwick Street towards the Town Hall.

Lieut-Colonel Wisden, on horseback, took command and led the troops down South Street and back again, followed by several hundred “roughs” totally unimpressed by this show of official force.

Returning to the steps of the Town Hall, Wisden tried several times to persuade the crowd to disperse.

Stones were being flung in all directions. Boys such as Arthur Swain, then only 13-years-old but who later became a nationally famous pigeon breeder, acted as ammunition carriers, taking stones from the beach to the rioters.

At 11.30pm, an ashen-faced Lieut-Colonel Wisden decided to read the Riot Act, the only time in Worthing’s history this drastic step has been taken. The cavalry were ordered to move forward and clear the streets. Their conduct, unlike that of the police, was later described as being “marked by a great deal of tact.”

In groups of 12 with truncheons drawn, the police followed through with a series of running charges. Unfortunately, they continued the length of South Street and several `really savage assaults’ were made on `peaceful and unoffending’ townspeople, who claimed they never even heard the Riot Act being read.

A pastry cook named Semandeni, whose shop was where the Royal Arcade now stands, came out to watch the rioting and had his head smashed by a policeman’s truncheon. He later died as the result of the injury.

Fifteen minutes after midnight the streets were clear. When the Salvation Army next paraded four days later, they did so under the protection of 104 special constables.

Three days after that, three men were sent to trial for `rioting and by force beginning to demolish Mr George Head’s house and shop.’

Incredibly, on September 7 the riots started all over again. George Head had his house wrecked by a mob for a second time in three weeks. For the second time he used firearms to defend his property and family but this time he was arrested, charged with wounding Edward Olliver and bailed for £400 to appear at Maidstone Assizes.

There, George Head appeared before the judges as both defendant and as chief witness against the three other charged men, who were each sentenced to four month’s hard labour.

Head did not even have to defend himself in court on the wounding charge, the jury deciding that his use of firearms to protect his family and property “was completely justifiable.” He was discharged.

The man who had the courage of his convictions and literally stuck to his gun, died a Salvation Army hero in December 1900. But not before he had successfully sued the town of Worthing, claiming that if the police had turned out on the first day his home was attacked most of the ensuing trouble would have been avoided. He was awarded substantial damages.

Members of the Salvation Army continued to face a bitter boycott in private life. Many were dismissed from their jobs and others were refused work. Local children amused themselves by playing at Salvation Army riots and singing parodies of the Army’s hymns.

The sordid affair was only ended by publication of an official town notice declaring: “Anyone subscribing to the Skeleton Army will be treated as a criminal and sentenced to three months hard labour without the option of a fine.”

It was a magic piece of paper that had taken a long time to prepare.