Get the Graf Spee!

ONLY a few days before the outbreak of World War Two in September 1939, Commodore Henry Harwood, RN, waved his wife goodbye at the gate of their home in Broadwater Street West, Worthing, knowing that war was imminent. Yet by no stretch of the imagination could he or his family have guessed the dramatic events he would experience before coming home to Worthing as World War Two’s first naval hero.

THERE had been many tearful farewells during the long Harwood naval career, which began before the outbreak of the First World War.

Long goodbyes became even more familiar punctuations in Henry’s life when in 1936 he was appointed Commodore of the Royal Navy’s South Atlantic Squadron. By then Mrs Harwood was no longer being left in Broadwater on her own, the couple having two children, Cyprian Henry Harwood, aged 10, and Stephen Chard Harwood, four.

By 1939 and the last day of his summer leave, Harwood knew he was going off to war, but neither he or his family could have envisaged the drama that would unfold in the coming weeks.

From the moment that war was declared on September 3, 1939, the whereabouts of Commodore Harwood was a naval secret not even his wife could share. At home in Broadwater she naturally assumed that as Commodore of the Royal Navy’s South American Squadron he was probably heading for that area.

It was not until a Saturday night in mid-December that Mrs Harwood learned of her husband’s exact location. Sitting in her Broadwater home listening to the war news on the radio she was surprised to hear the BBC announcer mention the name of her husband. He had just been responsible for the first major Allied naval victory of the war!

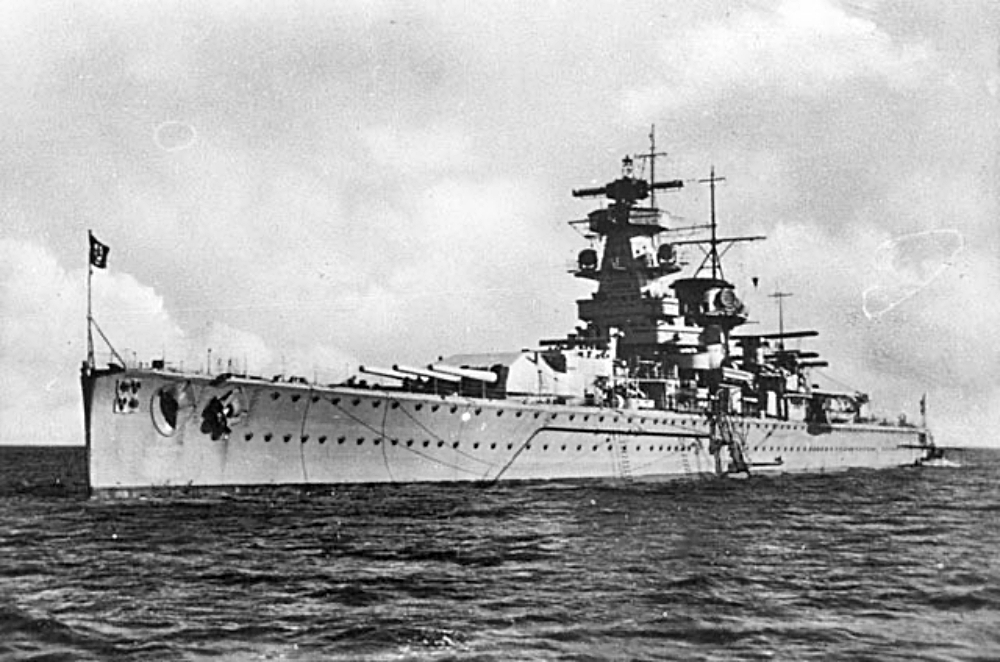

Against all odds, three Royal Navy warships under Harwood’s command – the cruisers Exeter, Achilles and Commodore Harwood’s flagship Ajax – had located the pride of the German navy, the marauding German pocket battleship, Graf Spee, in the vast open spaces of the South Atlantic.

That alone had been considered an almost impossible task but Commodore Harwood then decided to also close and engage the Graf Spee in battle, despite its superior tonnage, armament and firepower.

The running battle lasted more than 14 hours and began with everything loaded in favour of the legendary German vessel.

Graf Spee’s newly designed 11-inch guns had a range of 30,000 yards and could fire a 4708 lb broadside, while the Exeter had only eight-inch guns and Ajax and Achilles mere six-inch guns.

By using smoke screens to secure a degree of concealment and with their smaller guns able to fire more rapidly, the audacious Royal Navy trio under Commodore Harwood’s direction then fought their way into the history books.

The Graf Spee, which had roamed the South Atlantic unmolested for nearly four months sinking many unarmed Allied merchant ships, was now brought almost to a standstill.

On the night of December 13, 1939, Captain Langsdorff, the increasingly desperate commander of Hitler’s favourite warship, took her into the River Plate and neutral Uruguay’s Montevideo Harbour, hoping to repair the widespread damage the three allied warships had inflicted on her.

But the Uruguayan authorities told the German captain that if Graf Spee stayed more than a few hours she would be interned for the duration of war.

Lying in wait for her outside the harbour, the British cruisers – unknown to Capt. Langsdorff – had suffered their own extensive damage.

The Ajax, with Commander Harwood on board, had two of her four gun turrets knocked out during the battle while Exeter had lost three of her eight-inch guns and sustained more than 45 hits, many of them from shells three times the weight of those she could fire back.

One hundred members of her crew had been killed or injured.

The end came unexpectedly, as the Graf Spee sailed slowly out of Montevideo Harbour. Just beyond the three-mile limit of Uruguayan waters, she erupted in a vast explosion and sank beneath a mighty column of smoke that shot hundreds of feet into the air.

Captain Langsdorff had scuttled his vessel, fearing she would otherwise have probably fallen into Allied hands. He then committed suicide, knowing the fate Hitler would have waiting for him for losing the Nazi’s pride and joy.

Understandably, the happiest woman in Worthing that Saturday night was the wife of the Graf Spee’s conqueror.

“I am very proud of my husband’ she told friends who phoned with congratulations in the hours following the BBC’s news bulletin. Only by now Mrs Harwood had a further news item for them.

On hearing of the much-needed first British naval victory of the war, King George V1 had immediately promoted Commodore Harwood to Rear Admiral and appointed him Knight Commander of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath.