Working in the Dark

A heavy manhole cover shot high into the air and crashed back to the ground with an almighty clatter as Montague Street, Worthing, reverberated to a violent explosion.

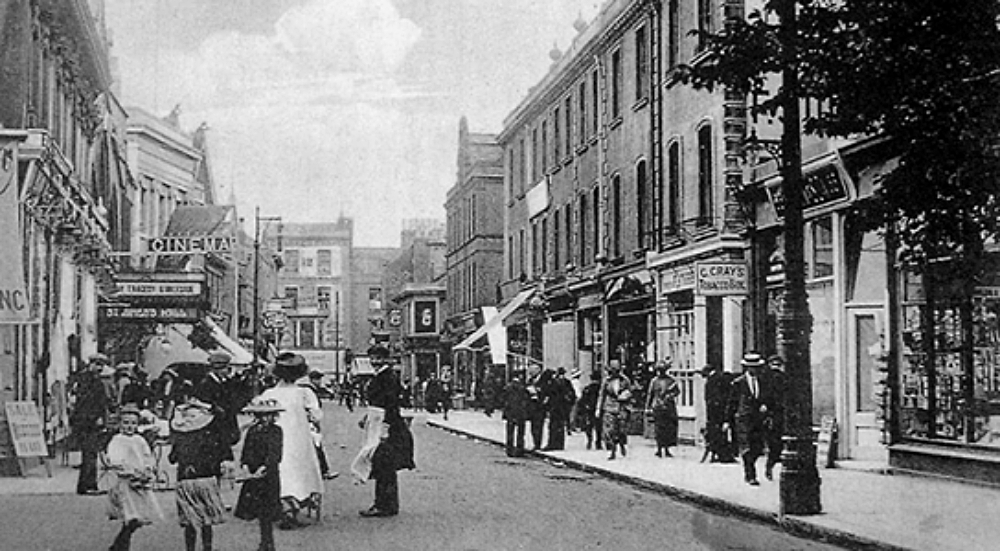

It was 1914 and must have sounded like an exploding bomb to the shoppers walking the town’s busiest street. In fact, the First World War was still three months into the future. But smoke and flames erupted “to quite an alarming extent” from the resulting hole in the roadway and to describe the result as panic and chaos would be an understatement.

A RELIABLE electricity supply is something we take for granted today, but for several years after Worthing Corporation invested a capital outlay of £32,500 to make electricity widely available to the public in 1901, breakdowns – and the inevitable blackouts that followed – were an all-too-regular occurrence.

But there had never been anything quite so alarming as the “big bang” and consequent town-wide blackout of May, 1914.

At that time, the town had three picture houses, showing what were contemporarily described as “pictorial displays of moving pictures”. There was the Winter Hall, St James’ Hall and the seafront Kursaal, later to become the Dome cinema.

Following the Montague Street explosion, all three were instantly plunged into darkness.

At the Winter Hall, someone foolishly shouted, “Fire!” which only intensified alarm among the crowded audience as, in near panic, they scrambled for the exits.

In the St James’s Hall cinema, where the current supplying the cinematograph lantern also ceased, manager Jack Andrews went on the stage to explain the cause of the failure and to avert panic.

In desperation, he tried a novel way to atone for the disappointment of the patrons. He burst into song.

“His effort was so appreciated”, a member of the audience reported later, “that when he made an offer to return all the money paid for admission, very few of the patrons demanded it”.

The abrupt lack of electric lighting upset a performance of Romeo and Juliet by the Glossop-Harris and Frank Collier Repertory Company, while at the Kursaal the “pictorial programme” in the first-floor Electric Theatre was abruptly halted.

In contrast, the crowd watching a rink hockey match in the adjacent Coronation Hall treated the entire incident in a relatively light-hearted vein. Perhaps typical of sportsmen of the day, they continued to watch the game with the aid of lighted matches!

It was subsequently discovered that the cause of the town’s first major electrical power failure was “condensation on the ironwork of a joint box in Montague Street”. In other words, a simple accumulation of water.

Postscript: Corporation engineers managed to restore power to all of Worthing’s 780 private electricity consumers later the same evening, though for several days the town’s electric lighting was described as “naturally rather jumpy and unsteady” – which caused considerable amusement among the many residents who, in the face of progress, had decided to remain loyal to the tried and tested Victorian gas-light system.

There was only a small increase in the number of electricity consumers in Worthing until the mid-1920s, when Durrington and other outlying areas were connected.

Worthing was finally linked up with the National Grid in 1930 and by 1933 the number of properties using electricity in the town had risen to 12,786.