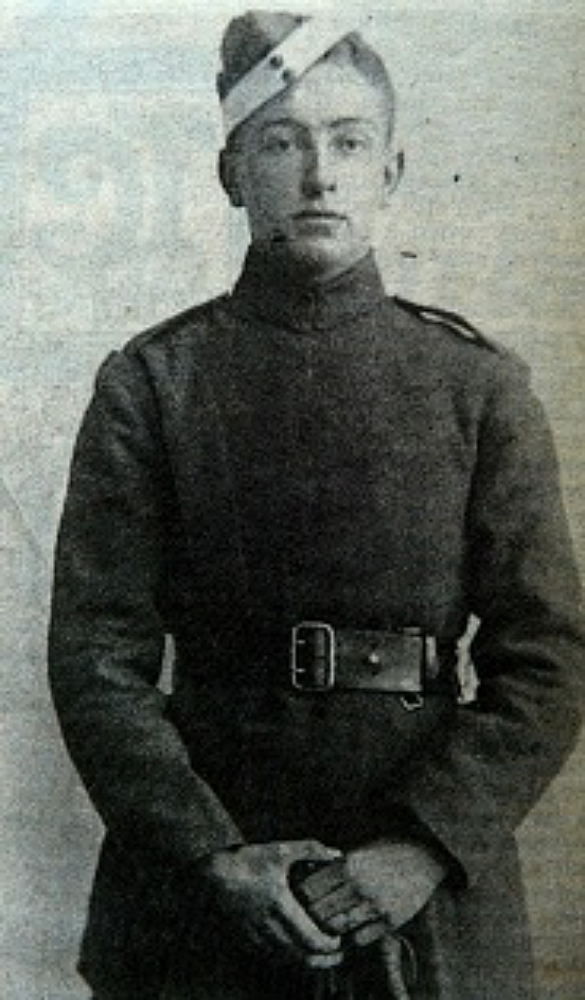

Gerald Dixon – on a wing and a prayer

GERALD Dixon lived out his retirement in a house in Marine Parade, West Worthing, convinced that, having been born at the very end of Queen Victoria’s reign, his generation witnessed more dramatic changes in the world than anyone before or since. Some people may argue with his claim, but, in relating Gerald Dixon’s personal experiences, Freddie Feest recalls the astonishing development of flying in the early “stringbag” days of World War One. Gerald was there, dreaming that he could become a pilot in what was wishfully dubbed at the time, “the war to end all wars”.

BORN in 1899 in Southport, Lancashire, Gerald Dixon spent his earliest years at Llandudno, Wales. It was at the age of 12 that Gerald visited Buxton, on holiday with his family, and saw a poster advertising the arrival of a plane flown by the famous pilot Gustavus Hamel. Together with 3,000 other people – none of whom had ever seen an aircraft before – Gerald watched in wonder as Hamel’s plane gently touched down in a field.

“I knew in that instant that flying was the only job I would ever want to do,” he said many years later. By the age of 14, I was aching to join the Royal Flying Corps, which had been born out of the Royal Engineers a couple of years earlier. With the outbreak of war in 1914, my ambition grew even stronger.

It was an age of great patriotism and a time when everybody believed that it would always be the other person who would lose their life.

Our schoolmasters all rushed off to be killed, in the belief that the war would be over by Christmas.

My chance finally came in September, 1917, when I went along to London’s Hotel Cecil and was enlisted as a Royal Flying Corps cadet.

I was sent first to Halton, near Wendover, for one month. On arrival, we were immediately promised our complete kit. In fact, we had to wait 10 days before we were issued with even cutlery with which to eat. But we were all young and eager and there was not a single complaint as we looked on it as just part of the war. At Halton, we suffered heavy inoculation doses, which made us all pretty ill. We then moved to Hastings for one month and learned a new ‘harsh language’ from the drill sergeants which, even today, I feel was unnecessary. I never felt we deserved the verbal abuse we received. Nevertheless, by the time we left Hastings, we had become a smart section and this tradition for drill and turn-out still exists in today’s RAF.”

“This was a time when the Royal Flying Corps was proving itself in France, despite Field Marshal Haig still seeing war in terms of cavalry rather than bombers. One particular admiral roared with laughter when it was suggested that one tiny aircraft might be capable of sinking his battleship.

Gerald Dixon’s next move was to Oxford, where he received lessons about airframes, engines and Morse code.

“I don’t believe the engine instructors really knew too much about their trade as I remember that any hole in an engine was always explained away as being either for lubrication or lightness!”

“From Oxford, I was sent on to Uxbridge, where we were the first course to study machine guns. I am still amazed to think that we managed to fly a temperamental aircraft and clear frequent machine-gun stoppages at the same time.”

“My most exciting move was to Catterick, Yorkshire, where I was finally to learn to fly on a DH6.”

“I use the phrase ‘learning to fly’ with great feeling, for in no way were we ‘taught to fly’.”

“During the First World War, 8,000 of our pilots were killed in training – more than were lost flying over the Western Front in France.”