Bumpy Ride to the Future

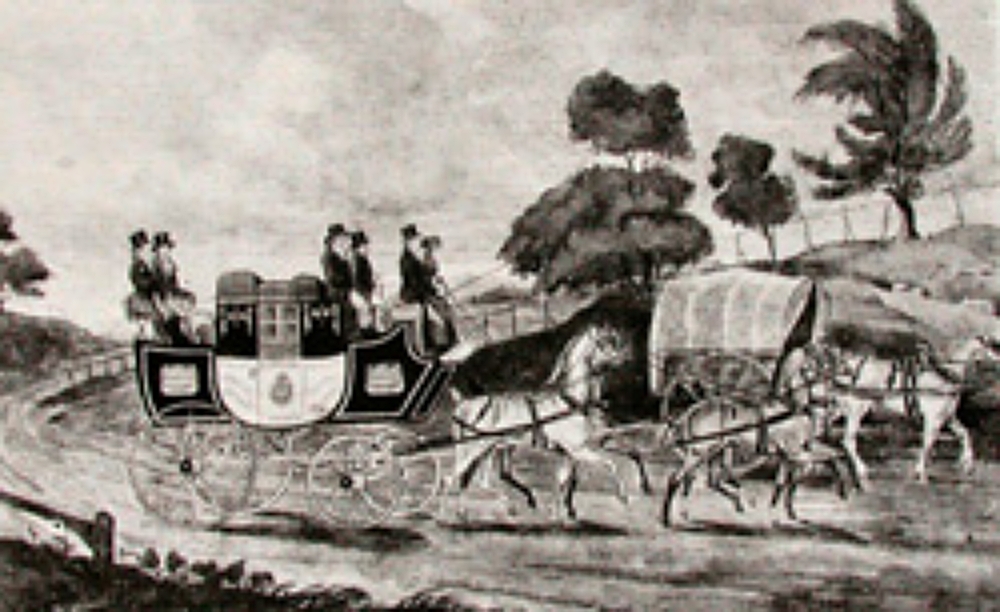

FOR most people who wanted to make a long journey across England in 1800, there was no alternative to the horse-drawn stagecoach. It offered a far-from comfortable form of travel, but in the next 25 years, great changes would take place.

These would not be attributable to improvements in coach design but to new scientific methods of road construction introduced by a new breed of road engineer led by McAdam, Telford and Metcalfe.

These engineers created hard, level road surfaces to replace the old, rutted and muddy lanes. The result? Far greater improvements in comfort for the long-distance traveller than any alterations made to the crudely-sprung horse-drawn conveyances themselves.

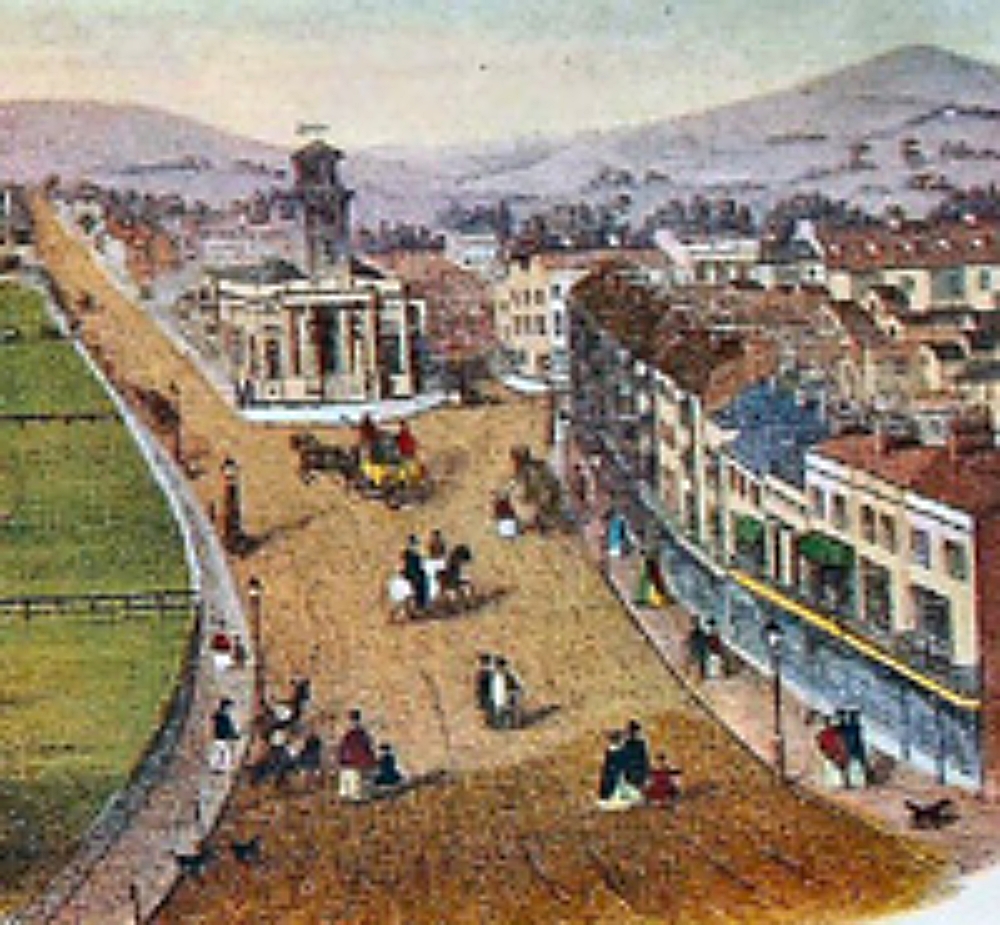

Freddie Feest picks up the story in Worthing’s South Street, which by 1800 had become an important hub of the fast-expanding south coast stagecoach network.

IMPROVEMENTS in road surfaces allowed the use of lighter and better-sprung coaches and proprietors were immediately willing to spend more money on better horses.

A light horse-drawn post-coach of the 1820s could weigh as little as 17 cwt and that’s barely the weight of a medium-sized modern car.

Unfortunately, it was still expected to carry 16 passengers and their luggage, with three-quarters of the weight loaded on to the roof!

This lighter construction and top-heavy design meant that broken wheels and axles and overturned coaches became an almost daily occurrence.

Horse-coach transportation was now reaching its peak of popularity and, fortunately, a superior class of driver was now coming into the business. By 1820, an intoxicated driver on the box was a rarity, whereas 30 years earlier, it had been rare to find one perfectly sober.

Coach driving began to attract amateurs of varying degrees of proficiency and a driver had to be a real artist on the box to satisfy the knowing coach proprietor. A practical improvement in coach design about this time that encouraged amateurs to take to stagecoach driving, was the fitting of springs to the box seat. Previously, the box seat had been fitted directly to the frame of the coach and the proprietors vigorously opposed the innovation on the grounds that if the driver was made too comfortable, he would always be falling asleep.

Even the most enthusiastic amateur driver could hardly survive a journey of 50 miles or more on an un-sprung seat.

While amateurs took up coaching for fun, there was another notable class of driver during this period – the professional gentleman drivers.

These were usually young men of good families compelled by extravagance or adverse fortune to earn their own living.

In earlier days, they might have taken to the road in a less law-abiding capacity but now the opportunity presented itself to do something in the stage-coaching line, the one thing in life they might be fit for.

Some set up as proprietors on their own account while others were employed by one of the bigger concerns, where a titled driver with a proven knowledge of horses was naturally an asset.

Though at first they were greatly resented by the older class of coachmen, their sheer driving ability quickly won respect on the road. With excellent manners and driving finely appointed coaches – many with silver-plated fittings and pulled by the best thoroughbreds on the road – they quickly gained the favour of the travelling public.

The busy Brighton-to-London road attracted the finest gentlemen drivers in all their glory and they added a brief but glorious episode to the pageantry of that highway. But two members of this class made a spectacular appearance even closer to Worthing.

They were the brothers Richard and John Walker, of Michelgrove, at Patching. The mark that Richard left on the local landscape will probably still be familiar to road users in the 22nd century.

After quarrelling with Mr George Cross, proprietor of the Bognor-to-London coach, over the sale of a horse, Richard Walker decided to set up a competitive coaching business.

While Mr Cross ran his coach through Arundel and Pulborough, the determined Mr Walker went to the expense of constructing a road as a shortcut between Arundel and the faster Worthing road so that he could get to London before his rival.

That shortcut road remains an invaluable link for today’s motor traffic and is still known as Long Furlong.

The coaching timetable for 1828 gives an idea why the clatter of horse’s hooves was so familiar in South Street, Worthing. This was where the main coach offices were situated at the time.

First coach for London left from 7 South Street every morning at nine. Another departed from 20 South Street “every forenoon at 10”.

Coaches for Brighton left 7 South Street each morning at 8.30am and 10.30am and a third in the afternoon at 3.30pm – all going through Shoreham.

A competing coach, named “The Dart”, left from an office at 22 South Street every morning at 10 and also passed through Shoreham.

A coach to Portsmouth departed from 7 South Street every afternoon at 1.30pm, while “The Times”, also based at 7 South Street, left each morning for Southampton, via Arundel and Chichester.

The Southampton “Times”, one of Crosweller’s Blue Coaches, was apparently a singularly unlucky one, prone to accidents. One of its last exploits, in 1840, had a tragic ending, when it overturned at the top of Salvington Hill and the driver was killed.

The 1830s were notable for some very fast-running coaches on local cross-country roads. A particularly fast coach, named “Nimrod”, covered the journey between Brighton and Portsmouth in six hours.

In 1831, the “Red Rover” covered the 138 miles between Brighton, Bath and Bristol in 15 hours. At the time, that was considered “extremely good going”.

Racing was a serious cause of many coach accidents. It was not always easy to restrain a driver on a fast road with good horses in front of him if he found himself being overhauled by a rival concern.

In 1810, two coachmen raced their coaches from Worthing to the Sussex Pad inn at Shoreham. Disregarding the protests of their passengers, they raced neck and neck. At Shoreham, the leading coach took the corner at Buckingham Farm too quickly and the driver, named Coles, was thrown off and killed.

In 1827, an accident occurred as one of the Worthing coaches was being taken out of the yard in Market Street. The horses took fright and galloped down Market Street and into High Street, then charged into a tailor’s shop. The horse-keeper, whose name was Sandall, tried to stop them but was thrown under the coach and had both legs broken.

It appears that too many accidents were due to horses being left unattended, especially outside public houses.

Worthing coachmen, although not considered “quite in the front rank”, were none-the-less a first-class set of drivers highly regarded by their contemporaries.