Thomas Henty – we have been here before

MANY imagine that today’s banking problems – largely blamed for the credit crunch – are a new phenomenon.

It may be small consolation, but as we move cautiously into 2009, it’s worth remembering that banks suddenly going out of business hardly constitutes a new hazard.

Sussex suffered many bank collapses in the late 1700s and early 1800s and these were not inconveniences to be quickly resolved by the government interventions and bailouts introduced in recent times. They were full-scale personal disasters on an unprecedented scale.

Freddie Feest recalls those times – and the man who many of today’s bankers might envy, who chose just the right moment to leave town with his finances intact.

PRIVATE country banks came into being in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, their aim being to provide a useful service that previously had been available only in major cities.

These local banks enabled their clients to raise short-term loans and provided a convenient way for customers to remit money from one part of the country to another, usually in payment of debts. They also invited customers to deposit relatively small sums at interest without having to invest directly in a commercial venture.

It was an idea that found widespread favour.

Many country banks were run by local businessmen, land owners or publicans – often several in partnership. They knew the majority of their clients personally and were often persuaded to make small loans “out of the goodness of their heart” to local residents with big families, very low incomes and almost no hope of being able to repay the debt.

Surely all too similar to a pattern promoted in recent times.

By 1810, there were more than 720 private country banks throughout England, some being operated on a relatively firm basis. So much so that at one point the value of a Bank of England £5 note fell to little more than £3 against notes of the most reliable country banks.

Sadly, there was little regulation of country banks and no control on the number of notes they could issue. Nor on the resources they had to maintain to meet their obligations.

Before long, bank failures became frighteningly common. A single bank failure could trigger a wave of panic as customers tried frantically to withdraw their money from other suspect banks, which collapsed in turn.

An old Sussex farming family named Henty was responsible for starting one of Worthing’s first banks, in 1808. One of its partners, Thomas Henty, had purchased his own 284-acre farm at West Tarring for £12,000 when he was only 21 years of age.

He was to prove an adventurous entrepreneur who today could be likened to a dot-com millionaire.

This was the Napoleonic period and produce prices were high. The Henty farm prospered and as his family grew, so did Thomas’ ambitions.

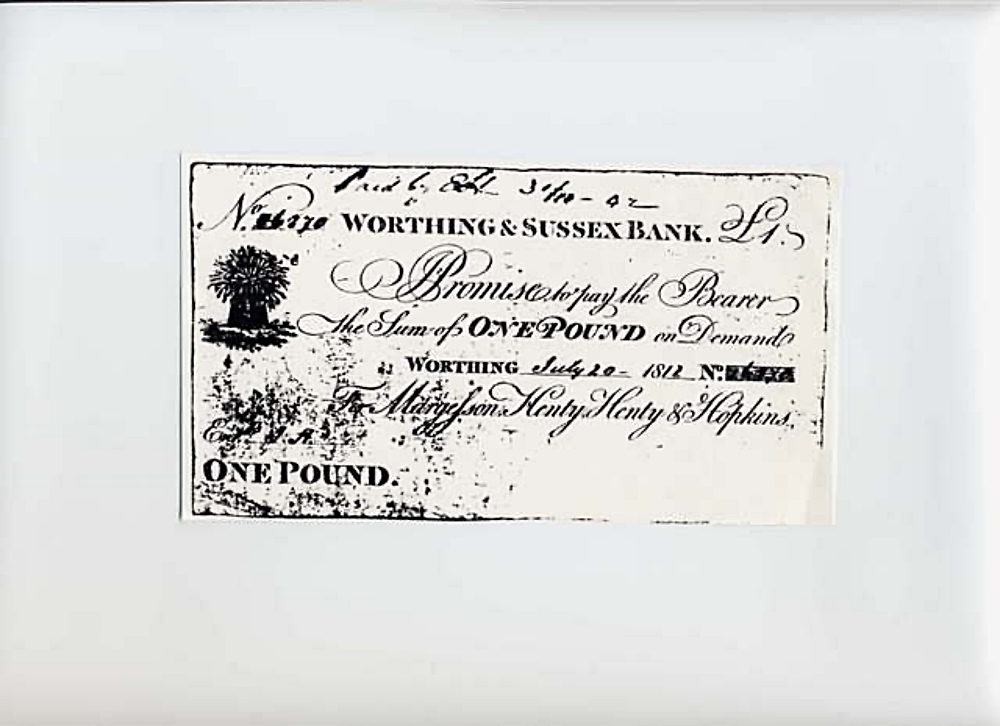

In partnership with his brother George, a relative named Oliver, a landowner called Hopkins – related to the Henty family by marriage – and Colonel Margesson, who was Henty’s senior officer in the Sussex Yeomanry, they started and ran the Worthing and Sussex Bank, with premises in Warwick Street.

In the early 1800s, a licence to issue notes cost only £30 a year, with stamp duty payable on each note. The Henty bank was partly financed by issuing its own £1, £2, £5 and £10 bank notes

For Thomas Henty, the Worthing bank was very much a family business and he was soon joined by two of his sons.

Unfortunately, none of these early small Sussex banks ever held sufficient cash reserves to stave off a run on their resources. Like some banks in very recent times, they survived through public faith rather than their own soundness.

Ten years after the defeat of Napoleon, the weakness of this financial system was put to the test. No fewer than 60 English banks failed and Sussex was badly affected.

Many bankers had a very lean time, made worse in Henty’s case by the theft from a Worthing to London stagecoach of a large parcel of his bank notes.

The incident had extraordinary repercussions for the Worthing entrepreneur and was to set him on a path that changed the history and economy of an entire continent!

With £4,000 of his capital invested in the Worthing and Sussex Bank, and his other businesses suffering from recession, Thomas Henty decided he could make a better life for his large family, which included seven sons, by taking them to Australia.

In June, 1829, three of Henty’s sons sailed for Australia in a ship of 340 tons loaded with livestock and supplies. These would be required to make a new home ready for the entire family, headed by Thomas Henty, who would follow a year later.

Emigration to the other side of the world was an end of banking for the Henty family, who had given Worthing one of the more reliable financial institutions of the day.

After Thomas Henty’s departure to Australia, the Henty banks in Sussex were carried on by partnerships led by nephews and descendants of the founder. Not until 1896 were they all absorbed into the much larger Capital and Counties Bank.

Meanwhile, in Australia, Thomas Henty’s son Charles founded the Bank of Australasia and became its managing director. Another son, James, who had been manager of the original Worthing and Sussex Bank, became a director.

Two other sons, Edward and Francis, also made their way into the Australian history books by founding the colony of Victoria.

Thomas Henty decided to devote most of his time to his first love of farming, breeding thousands of Merino sheep from the few animals he had taken over from Sussex.

Within a few years, the entrepreneur from Worthing had again displayed his magic business touch by starting the Australian sheep farming and wool industry, which for the next 150 years was to be that country’s greatest earner.