Down to earth with a bump

GERALD Dixon went into World War One as a young lad with one ambition. He wanted to fly. By 1917, he was just old enough to enlist in the Royal Flying Corps as a cadet.

It was, as he recalled several decades later, after retiring to Worthing,

“An age of great patriotism and a time when everybody believed that it would always be the other person who would lose his or her life”.

He was posted to Catterick, Yorkshire, where he promptly found himself in a two-seater “stringbag” training aircraft, occupying the observer’s position behind an instructor.

“They called it training, but there was no way I could see what the instructor was doing and, with the roar of the engine and the howl of the wind, his instructions over the communicating rubber tube were unintelligible…”

LIKE many hundreds of other would-be pilots during the First World War, when Gerald Dixon made his first solo flight, he had, in his own words,

“I had absolutely no idea what to do, If you didn’t happen to have a natural aptitude, you ran the risk of being killed. While at Catterick, I made great friends with Francis Clarkson. Although we went our separate ways, with Francis being posted to fighters while I moved on to bombers, it is typical of those early pioneering days that we have remained lifelong friends.

“I believe that the signing of the Armistice in 1918, while I was still at Catterick, saved my life, for it has since been revealed that in response to the disastrous raids by Germany’s Gotha bombers on London, it was planned to retaliate with raids on Berlin. The chance of flying our aircraft safely to the heart of Germany and back, under attack by German fighters, would, in my opinion, have been nil.”

During his training, Gerald had only one serious crash, which, he was the first to admit, was mainly of his own making. He explained: “I was so busy taking photographs from my aircraft that I never noticed an increase in the wind.

“It was soon blowing so strongly that I had no idea how I was going to make a controlled landing. At a height of about 50 feet, my plane suddenly turned upside down and, before I knew it, I had struck the field. “Although I was completely doused with petrol, no fire took place and I escaped unhurt.”

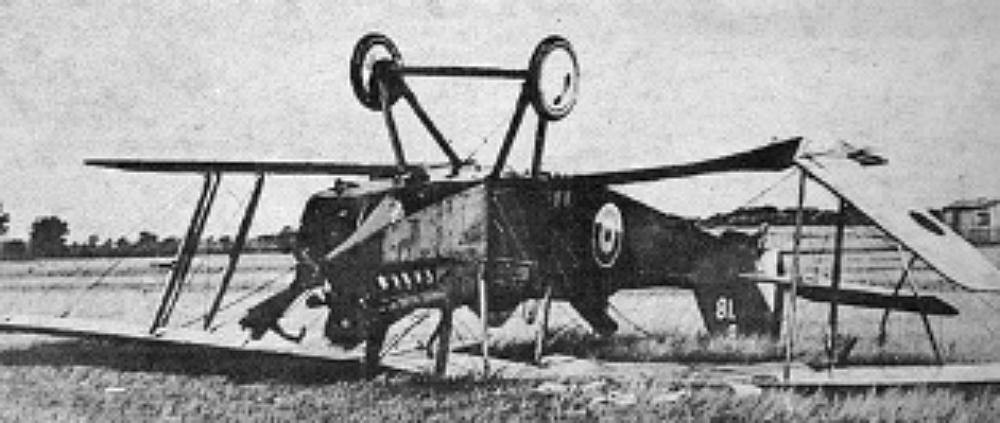

From Catterick, Gerald was posted to No 2 Fighting School near Redcar, Yorkshire, where he enjoyed a variety of so-called “stringbag”aircraft, including the SE5, Sopwith Pup, Sopwith Camel, DH4 and DH5.

Gerald was demobilised in 1919 and always remained angry that young men who had been willing to die for their country in World War One found themselves unemployed, with no government help.

Eighteen years later, seeing the threat of war looming yet again, he joined Heston Aero Club, off the Great West Road, where it cost £2 an hour to hire an aircraft.

There, after only half an hour’s practice, he made his first solo flight in 18 years at the controls of an Avro Cadet, flying over the present site of Heathrow Airport.

He recalled: “Then, there was nothing to be seen but cabbages and allotments.”

His flying experience was called upon when World War Two broke out. In the following four years, he regularly flew Anson reconnaissance aircraft and Wellington bombers and was twice mentioned in despatches.

In retirement at Worthing, Gerald often marvelled at the changes in commercial aviation since that day in 1917 when he first flew solo.

“Today’s jumbo airliners carry 600 passengers compared with the De Havilland 9 bombers of the First World War, which were converted in peacetime to carry two passengers on flights to Paris.

“They didn’t, of course, always make it to Paris, because although the air-frames were sturdier than many people have since made them out to be, the unreliable aircraft engines ran into trouble, often because of dirty petrol. Even in a car of that time, you could expect to stop after half an hour to give the carburettor a blow-through; this may have been all right on the road, but it was not recommended when flying high in the air!”