It’s time we gave Selden credit he deserves

HIS name has been given to a local pub, a school and several roads, but just who John Selden is, or was, remains a total mystery to most Worthing residents.

Many pubs are named after buccaneers, local philanthropists, famous military men or even Victorian sportsmen – but a jurist? For that’s what John Selden was, a person versed in law and, in his case, particularly in the theory of law.

You might conclude that his job sounds boring, that he was an uninteresting man and no wonder his place in English history is so low-key. We prefer to learn about the glamorous people who won military battles, built the British Empire, were involved in royal scandals or more infamous deeds, or gained accolades as great sportsmen.

Freddie Feest believes the time has come to give John Selden his proper place in history, especially as he was born locally and lived in or around Worthing for much of his turbulent life.

JOHN SELDEN was born on December 16, 1584, in a cottage called Lacies, at Salvington, today better known as part of Durrington.

He happily grew up on his father’s 80-acre farm, though country life was to have little influence on his future.

The cottage was thatched and timber-framed, with flint walls and red brick courses. It survived as one of Worthing’s oldest buildings until criminally demolished by developers in 1954.

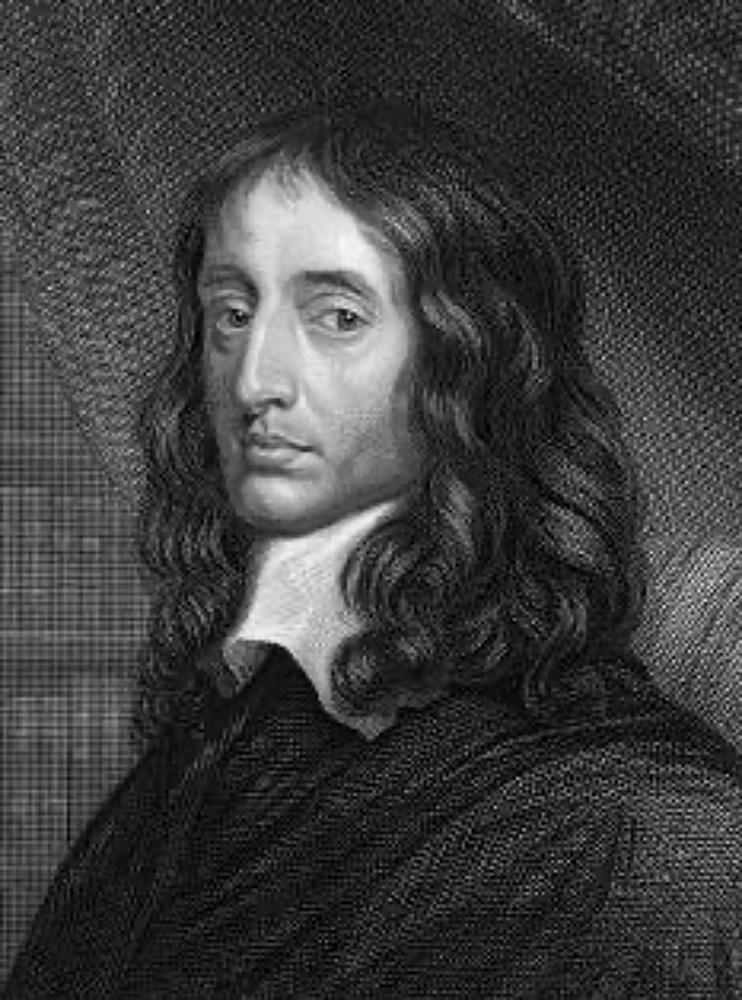

John was a handsome, sharp-featured lad, studious and a lover of music. His accomplishments with the violin played no small part in gaining him a wife whose social position was somewhat superior to his own.

She was Margaret, only child of Thomas Baker, of Rustington, and remotely descended from a knightly family of Kent.

Like so many controversial budding politicians, it was while studying at Oxford that young John discovered and rationalised ideas that propelled him into a leading role in the unrest that led to the fatal clash between Parliament and King Charles 1.

As a writer and scholar, Selden was determined to achieve a reputation among his contemporaries. In the murky shadows that led to the English Civil War, his rise to fame was meteoric – and his journey upwards was anything but boring.

On the way he flirted with treason, was imprisoned several times in the Tower of London, changed sides in the English Civil War and became a major influence in condemning King Charles I to the executioner.

By the time he was 23, Selden had impressed his peers by writing a book about the civil administration of England before the Norman conquest, emphasising that government of the country should be the joint concern of king and Parliament – a theme he would constantly return to in his future political career.

Before being called to the Bar in 1612 at the age of 28, he also wrote Titles of Honour, a book that remains a work of reference even today.

This was a time of great English constitutional controversies and the discontents, which a few years later ended in civil war, were already forcing themselves on public attention.

Although Selden was not in Parliament at this time, he was the instigator and probably the draughtsman of the memorable “protestation on the rights and privileges of the House” affirmed by the Commons on December 18, 1621.

Thus, at the age of 37, the lawyer who until now had mostly confined his work to the dreary task of conveyancing and hardly ever appeared in court, began delving publicly into the legal wrangling between King and Parliament.

As a direct result and in the company of several Members of Parliament, he was locked up in the Tower of London, with mutterings of “treasonable behaviour” ringing in his ears.

It taught him a sharp lesson – that there are two ways to tackle any dispute.

Within two years, he had become a Member of Parliament and by playing a prominent role in the impeachment of the powerful protestant George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, curried a degree of favour with the high church King Charles 1.

But in 1628, having been returned to the third Parliament of Charles 1, he was largely

responsible for drawing up the House of Commons Petition of Rights, making it illegal for the king to raise taxes without agreement of Parliament, or for anybody to be imprisoned without trial.

He was again slapped in the Tower and this time his intimate acquaintance with England’s most infamous prison was to last for eight months.

It was at this point that Selden revealed his true political skill and shrewdness.

While the world outside was consumed by the momentous constitutional conflict between King and Parliament, Selden was safely in prison devoting himself to the study of “antiquarian and oriental matters”.

The shrewdness of this move was that Selden had no need to jeopardise his future by declaring where his loyalties lay.

In 1635, however, Selden flirted with the Royalist cause, though it was a loyalty that lasted less than five years. By 1640, he had reversed his political position and entered what became known as The Long Parliament, representing Oxford University.

He took an important role in the Commons impeachment of Archbishop William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1640. Laud not only supported the un-Parliamentary policy of Charles 1 but also persecuted Puritans, alienated the property classes and virtually precipitated the English Civil War.

Thanks in part to John Selden’s legal arguments, Laud was sent to the Tower and beheaded.

Finally, Selden, who by now had become one of the most persuasive opponents of Charles I’s claim to divine right, was prominent in presenting the case against the King himself, which led to the execution of Charles in 1649.

From that date, John Selden took little part in public matters. He continued to write in retirement. Though never again expounding the benefits of England’s “ancient constitution”, he never failed to take any opportunity to support the rights of Parliament.

He died on November 30, 1654, at the age of 70 – his name forever to be remembered by lawyers but quickly lost in obscurity so far as the general population was concerned

But a dull man who led a boring life? I don’t think so.

Footnote: Selden’s Cottage, in Durrington, was damaged by fire in 1963 and, after a tragic town council decision, was demolished and replaced by a bungalow.