The tough struggle for justice

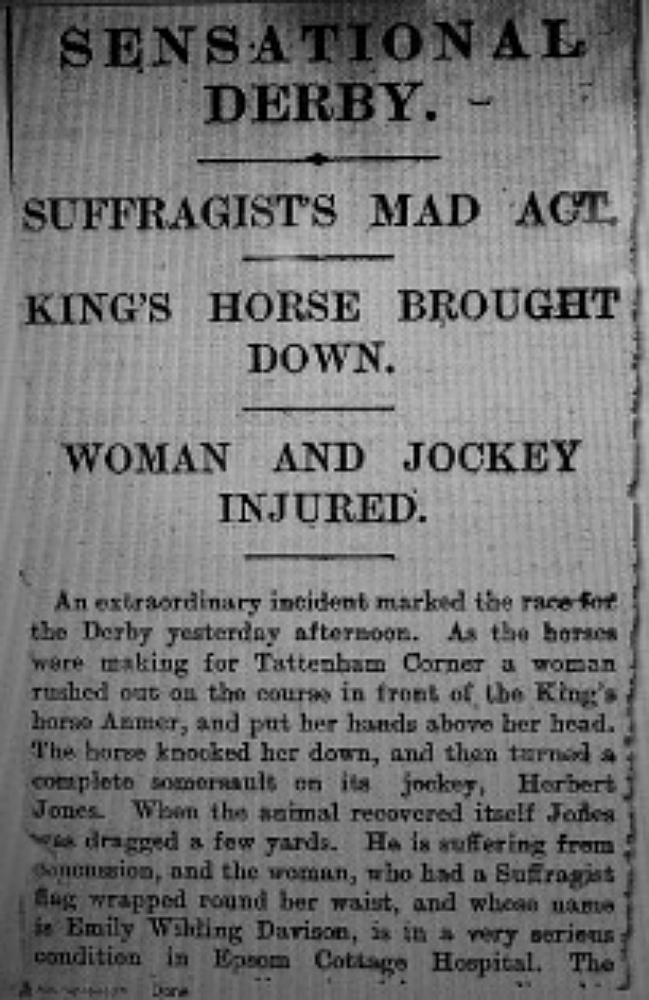

MRS Pankhurst chained herself to the railings of the Prime Minister’s home in Downing Street. Emily Davidson (who, unknown to most people, had worked as a teacher in Worthing) was killed when she threw herself under the King’s horse during the Derby at Epsom. And there were riots in the streets of London.

That’s really all the majority of people today recall about the long and tortuous struggle that women had in the early 1900s to win the right to vote.

But back in the Spring of 1913, the disturbances created by suffragettes in Hyde Park, the militancy shown by women fighting to be allowed to vote and the force-feeding of them in prison were all heated topics of conversation for early Spring holidaymakers arriving in Worthing.

So it was hardly surprising there were queues and a capacity audience at the meeting called by Worthing suffragettes at St James’s Hall, in Montague Street, on April 28th of that year.

REFLECTING on earlier riotous events, Worthing’s suffragettes took elaborate precautions to prevent disorder at that Monday afternoon meeting.

Both entrances were strongly guarded by police and more were stationed in the hall and around the gallery.

Although women were encouraged to attend, men were only permitted on the personal invitation of supporters of the cause who were willing to guarantee their good behaviour.

The organisers claimed to have set the stage for a peaceful meeting. Many local residents had not the remotest intention of attending, but if they had would certainly have taken strong exception to the purple and white scroll bearing the inscription “God Befriend Us For Our Cause Is Just”, which occupied a prominent position at the back of the stage.

Recalling what was said at that meeting is probably the most reliable way of judging the feelings of women at the time..

Mrs Israel Zangwill presided at the Worthing meeting and admitted from the outset that suffragettes did not claim that the enfranchisement of women would make a perfect world. It was merely a means to an end.

“When women get the vote,” she declared, “it is going to do bring about immense changes. It will improve the position of men as well as women because, at the moment, men have unfair privilege and unjust power and that is a very bad state of things for any section of the community.”

She added that in the American Civil War it was not only the slaves but also the slave-owners who were set free.

“The vote on women’s suffrage is also likely to affect indirectly women’s wages as the sweated industries are almost entirely women’s industries.”

Mrs Zangwill thought it was “absurd” for men alone to legislate for children and likened it to women legislating for the Navy.

She cited “the ridiculous spectacle of men solemnly discussing in Parliament the height of a nursery fireguard or whether a baby should be allowed to sleep in its mother’s bed.”

Cheers greeted Mrs Zangwill’s refusal to make excuses for referring to militancy. “It is a burning question of the day. It is a burning question of the day in more senses than one, though I have not personally taken part in it.”

She told the audience that even if she disapproved she had to admire the courage, endurance and self-sacrifice, which lay behind it.

“There can be little pleasure in shouting at Cabinet Ministers, being set upon and knocked down, dropping paint into letter boxes, sprinkling acid in golf courses, setting fire to shavings on an empty racecourse stand and running the risk of prison, all of which some of our members have done.

“Prison, however, is no pleasant place. Suffragettes have even been willing to suffer the torture of forcible feeling and I wonder how women many in Worthing today would be willing to face such sacrifices?”

“When votes for women are achieved,” she concluded, “women will once again be peaceful and law-abiding citizens.”

To emphasise the support some men gave the suffragette cause, the next speaker, Reginald Pott, declared, “If the Government misgovern women without their consent, they are justified in behaving as outlaws.”

Mr Pott added, “Britain fought for her outlawed sons in South Africa a few years ago and now women are fighting for their outlawed daughters in Britain.”

Barbara Wylie, who had recently taken part in the Hyde Park “disturbances” said suffragettes were accused of going beyond the law but history had shown that no decent laws had even been passed until a section of the people had gone beyond the law.

“Men are such self-centred animals that it is almost impossible to knock into their heads that although conditions had changed for them they are exactly the same as women.”

Profile of Worthing’s “revolutionary” teacher.

MILY Davidson was born in 1872, Successful at school, she won a place at Holloway College to study literature but two years later was forced to leave when her recently widowed mother was unable to pay the £20-a-term fees.

Emily found work as a schoolteacher in Worthing and eventually raised enough money to attend London University.

As a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, she took part in her first demonstration as a suffragette in 1908 and was first arrested the following year while attempting to hand a petition to Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith.

Arrested again four months later when she tried to interrupt a speech by Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, she was jailed for two months for stone throwing. Once again she went on hunger strike and was released.

A few days after leaving prison she was again arrested while throwing stones at Lloyd George’s car. They were wrapped in Emily’s favourite words, “Rebellion against tyrants is obedience to God.” She was sentenced to a month’s hard labour in Strangeways Prison.

Attempting to avoid being force-fed during her hunger strike she barricaded the door of her prison cell but a prison warder forced the nozzle of a hosepipe through a window and filled up the cell with water.

Emily was willing to die but before the cell had been completely filled the door was broken open. She later sued the warders at Strangeways and was awarded forty shillings damages.

It was while serving a further six months sentence for setting fire to pillar boxes in December 1911 that Emily became convinced women would never win the vote until the suffragette movement had a martyr.

At the Derby in June 1913, she ran onto the course and tried to grab the bridle of the King’s horse, Anmer. The horse hit Emily and fractured her skull. She died without regaining consciousness.