Elizabeth Crawford, a woman of substance

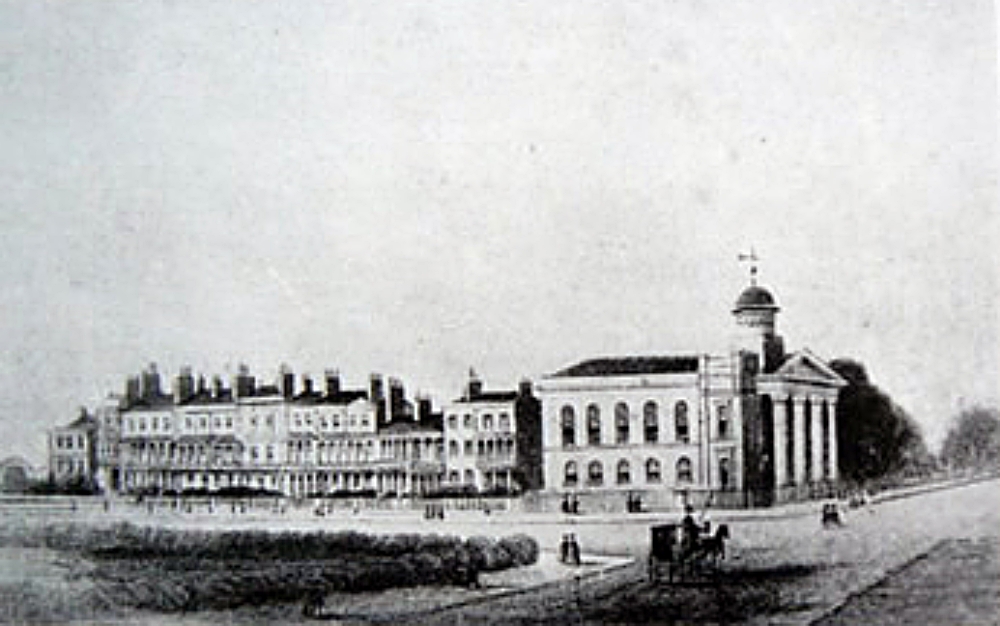

IN the early 1800s, Worthing was a semi-fashionable community of 3,725 inhabitants, enjoying the occasional favours of princesses, but fighting shy of such garish splendours as the Prince Regent took with him to Brighton – both reasons why the town appealed to Mrs Elizabeth Crawford. A third incentive was Worthing’s economical cost of living.

As the wife of a wealthy businessman, Mrs Crawford had enjoyed every aspect of London “society”, but when her husband died and unexpectedly left very little money, she was forced to live in much reduced circumstances.

To Mrs Crawford and her three daughters, “maintaining a certain position in polite society” had become extremely important and Worthing appeared to offer this possibility, even to people of much-diminished means.

The town boasted a stylish quarter-mile esplanade, commodious, warm baths, some 60 bathing machines, two “respectable” libraries and even a theatre. What more could a widowed Victorian mother ask for?

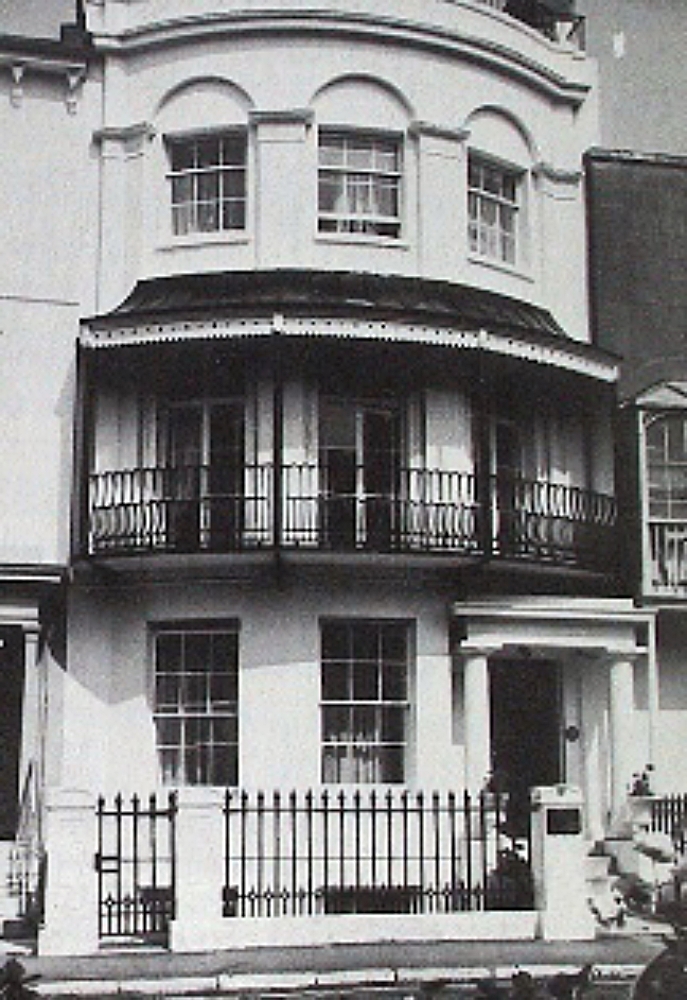

SINCE 1812, Worthing had worshipped in its own Chapel-of-Ease – later to become St Paul’s Church – and westwards from this building stretched a row of new houses called Ambrose Place.

Here, each house enjoyed front and rear gardens and additional ground on the south side of the road, very much as they still do nearly 200 years later.

The Crawfords agreed it was as pretty a spot as they could possibly find – and promptly rented Number 13 for £55 a year.

They came to love the road so much that it was here they were to spend the rest of their lives, “bound together in close affection while preserving their individuality of character evident in their subsequent handwritings”.

Having gained diverse experiences at home and abroad, Elizabeth Crawford was endowed with a love for the society of her fellows and the role of hostess.

She felt blessed with daughter Eleanor, who, although highly strung, was a sensitive and a gifted musician. Second daughter Martha “was made up of good nature and good works within the compass of her modest means”.

In contrast, Matilda Louise, only just 16 when they arrived in Worthing, found her delight in open-air exercise, particularly scampering on horseback over the Downs.

Contemporary records emphasise that only with good housewifery could these various activities be maintained at a time when it cost 4d to clear a fall of snow and £2 6s 9d to paint a house. Fortunately, the family’s circumstances were eased in the spring of 1831 when “certain funds fell due to them” on the death of Mrs Crawford’s brother-in-law. Which was fortunate as, by this time, many guests were calling socially at her house and had to be appropriately refreshed and entertained.

In 1835, the larger house next door, 14 Ambrose Place, became vacant and the Crawfords were able to purchase the freehold and move in almost immediately. It was an occupancy continued by Crawford descendants for many generations.

The four Crawford ladies of Ambrose Place were avid communicators and, through their many letters, left a fascinating personal picture of early 19th-century Worthing.

In a letter to her son, Robert, she wrote: “The Walshes, Kings and Coddingtons were at our party. We collected 38 people, including 19 gentlemen – a wonder for Worthing, where the majority are generally petticoats’’. I regret we shall not see your dear wife. If she could bring the infant with her, the two boys might come on top of the stage (coach), recommended to the care of the coachman.”

To her daughter-in-law, Mrs Robert Crawford, she observed: “We were very pleased with George (Robert Crawford’s eldest son). He is, indeed, a fine boy, but I do not like him going to the theatre by himself; there are so many worthless women there that may seduce him.”

A family acquaintance, Charles Lamotte, brought Matilda Crawford a severe reprimand from her mother, after she was seen “gallivanting with him on the Chain Pier at Brighton”. He was described to Mrs Crawford as “a dapper little beau with a protruding chin, in whose countenance the most solemn gravity constantly pourtrays (sic) the anxious lover”.

A note from middle daughter Martha Crawford, to her sister-in-law, Eliza, observed: “Such great alterations continue to be made in Worthing by the addition of new buildings that if we remain in Ambrose Place many years longer we shall be almost in the centre of the town.”

“You may remember at your first visit to us in Ambrose Place turning your pony to graze in a field behind our house – in that field now stands two gentlemen’s houses, with stables and walled gardens, and a third is soon to be erected. Sixteen or 20 houses are now building to the west of us in what used to be called Heene Fields.”

Elizabeth Crawford wrote many letters to her daughter-in-law during the social and political unrest of the 1830s. In one dated November 30, 1839, she was clearly alarmed, writing: “We are all truly anxious and mobs are going on in this country and, if it continues long, it must ruin everybody and breed a famine.”

Mrs Ann Sidebottom, in a letter to her sister, Elizabeth Crawford, in May, 1832, declared: “I think the world is gone mad – everybody seems to dread an explosion – though your account of Worthing gaieties give no symptom of evil, I shall be glad to hear that you all continue safe. To be sure women can do so little that they may be safe in their insignificance.”

But there were lighter moments in Victorian social life – and occasional deceptions.

Martha Crawford revealed to her sisters, Eleanor and Matilda Louise, in June, 1838: “I have ventured to give one tea party. My guests were the three Messrs Needham. I asked them to accompany me in a walk and return to tea, so, with the addition of bagatelle, music, cake and wine, we were very comfortable.”

“I did not tell them the wine had been opened above three weeks and was Marsala and Sherry mixed together and put in a small decanter to make it look more. They quaffed it very contentedly…”

Near the end of her life, Mrs Elizabeth Crawford contributed to the building of Christ Church, at the west end of Ambrose Place, but she died before its completion and was laid to rest in Broadwater Church in October, 1841.

None of the three Crawford sisters ever married. Eleanor, the eldest, died in 1867 at the age of 77 and Martha followed only 10 days later at the age of 69. Matilda Louise died in 1886, aged 81.

All three are buried at Christ Church, within a few yards of the house that for so long had been their happy home.