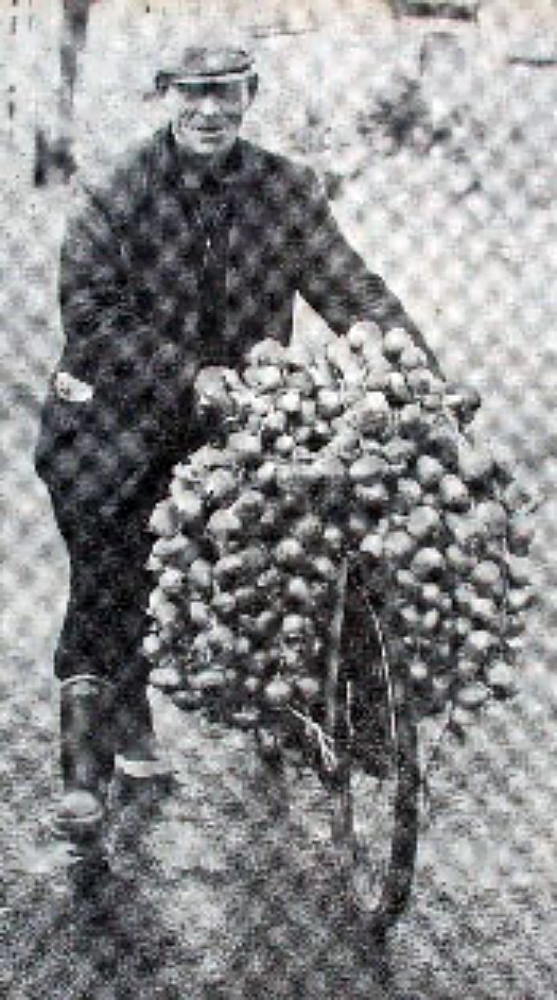

Rene Pouchard – he really knew his onions

HE didn’t look so very different from any British workman cycling to work first thing in the morning – as many still did half a century ago.

His cloth cap pulled down over his roughly shaven face, morning paper already well-thumbed, bulging from his jacket pocket – and strings of rustling onions dangling from the handlebars of his ramshackle bike.

Rene Pouchard was a familiar sight in many West Sussex coast towns during the 1950s and swinging ’60s. He was one of the onion sellers of Brittany, and his regular customers included the big hotels, restaurants and homes that relied on regular visits for their supplies of onions, Rene and his successors don’t come around any more. Freddie Feest recalls the Frenchman who became a Sussex legend in his own cycling time.

EACH year, for more than half a century, Frenchman Rene Pouchard crossed the English Channel in early summer and spent six months acting out the Englishman’s idea of what 50 years ago was the most typical Frenchman of all, the Breton onion man.

Together with 14 of his compatriots, some with wives and children in tow, he left his home town of Roscoff, near Brest, each July with the first load of onions and sailed for England.

From his base in a narrow street of Portsmouth, where he and his friends made their home for the following six or seven months, M. Pouchard and the others set out by train each morning, usually in an easterly direction. His initial destination, a station in West Sussex.

As soon as he left the railway station, he would be on his bike, surrounded by voluminous bunches of onions suspended precariously on the handlebars, and began another day’s work.

The last time we met, M. Pouchard had been visiting his regular Worthing customers and was about to make for “la route Shoreham”, as he put it.

“My clients in Worthing are all over the town,” he said, with a sweeping gesture.

The price he asked for his onions depended on the length of the string, the time of year and quality of the onion.

Only an occasional dropped “h” and an un-English wave of the hand betrayed M. Pouchard’s nationality.

His accent was barely discernible, not surprising when he spent half his year on this side of the Channel and the rest on the other. “From January until early July, we work on the farms around Roscoff, growing cauliflowers, potatoes and artichokes,” he said.

At the mention of artichokes, a grim smile flashed across his face and he began to tell about the bonfires of artichokes that were lit all over Brittany earlier that year when prices reached rock-bottom and farmers refused to sell.

M. Pouchard had no family problems, like some of his fellow countrymen. When asked if he was married, he replied: “Not guilty.”

During the 40 years he had been coming to these shores, he had returned to France only once at Christmas time.

He always found the people of this country very friendly to deal with. “I like the English very much,” he said firmly. “But, of course, there are the bad and the good in my country as well as yours.”

And why, for so many years, had people preferred to buy their onions from this man, rather than the shops in Worthing?

“Apart from the fact that it is more convenient, our onions are the best,” he replied with a wide grin.

One suspects, also, that they looked forward to these visits from a salesman whose selling tactics had no affinity whatsoever with the take-it-or-leave-it attitude of most British shop assistants in those days.

The onions used to sell themselves. The fact that the salesman was a Breton made the transaction only more interesting.