‘Stay-at-homes’ who made rail progress

THE Henty name is a familiar name to many Worthing residents. Best known are those Hentys who, in June, 1829, sailed to Western Australia with their father, Thomas, in a 340-ton sailing ship, the Caroline.

In those days, convicts transported from Britain largely populated Australia. Thomas Henty and his sons played a major role in transforming that land into one of the most appealing and prosperous on the planet.

But that was not the end of the Henty story. Few people know of the debt Worthing owes to some members of the Henty family who stayed at home in Britain. They were largely responsible for the railway coming to Worthing in the middle of the 19th century and transforming a sleepy seaside village into the largest town in West Sussex.

when Thomas Henty sailed for Australia, it was his brother, George, who remained in Worthing, perhaps convinced that his family of seven daughters and five sons might have been more than the budding colony of Western Australia could handle.

Two of George Henty’s sons, George junior, born in 1803, and Edwin, born 1805, were to play important – though today largely unremembered – roles in the economic development of Worthing.

Both became partners in the family’s Worthing banking business, by now known as Margesson, Henty, Henty and Hopkins, with a head office in Warwick Street, Worthing.

On the death of George Henty senior, in 1829, his younger son, Edwin, inherited the lease of Ferring Farm, where, according to the census of 1841, he employed five servants – a teacher, two nursemaids, a cook, housemaid and a butler.

Meanwhile, Edwin’s brother, George, became one of the Worthing commissioners administering the town (the Town Commissioners pre-dated the Board of Health, which eventually became the town council) and a partner in the family bank that was now expanding, having opened branches in Arundel, Steyning, Horsham, Littlehampton and Crawley.

Why, you may ask, did Edwin inherit the farm instead of his older brother, George?

It has been suggested that as a commissioner of Worthing, George had the power to release the ecclesiastical manorial holdings, thus leaving Edwin free to purchase the freehold of the farm.

In fact, George had a more pressing and potentially far more profitable venture on the horizon.

As a Worthing commissioner, he had been lobbying Parliament to establish a rail connection to Worthing, though, so far, Parliament seemed reluctant to extend the line to anywhere west of Shoreham.

In today’s world, George would have been barred from all discussion on the matter because of his conflict of interests.

On the one hand, as a Worthing commissioner, he would be involved in granting permission for any extension that might go ahead and on the other hand he was co-owner, with his brother Edwin, of the Brighton Chichester Rail Company.

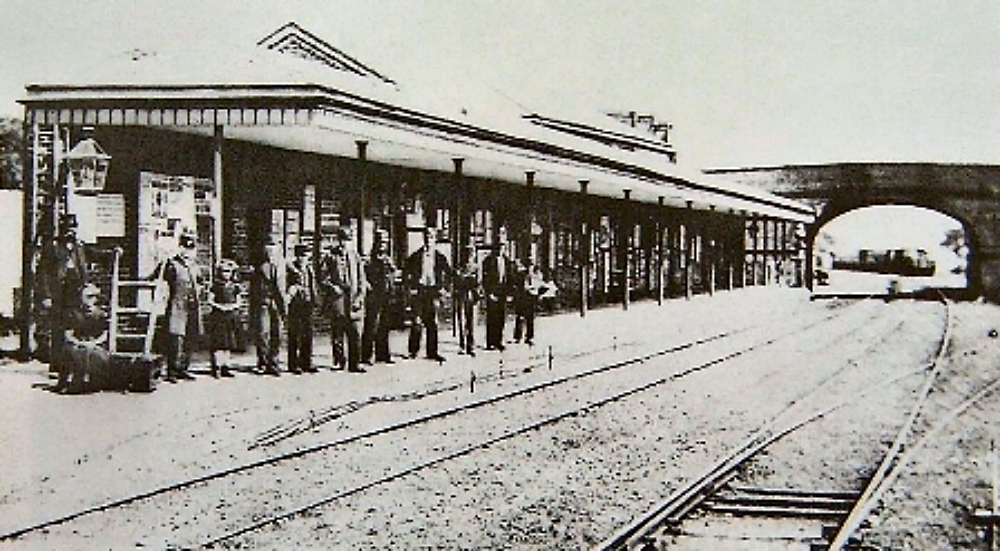

Surprise, surprise, when the railway’s extension scheme to the west was approved in 1844 it was the Henty-controlled company that was granted the concession to build the new line from Shoreham, through Worthing to Chichester, though they shrewdly changed its name to the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway.

Much of the money to carry out the plan (£285,000 – a massive sum in those days) was provided by the Henty family bank. It proved a nice little earner in the days when banks made most of their profit from interest on loans.

The stay-at-home Hentys were quick to learn the ways of influencing local politics, much as their relatives had done in Australia.

They particularly learned from the arrest of George Henty senior for smuggling and hiding contraband gin at his Ferring property in 1818.