“Death ray” that was radar

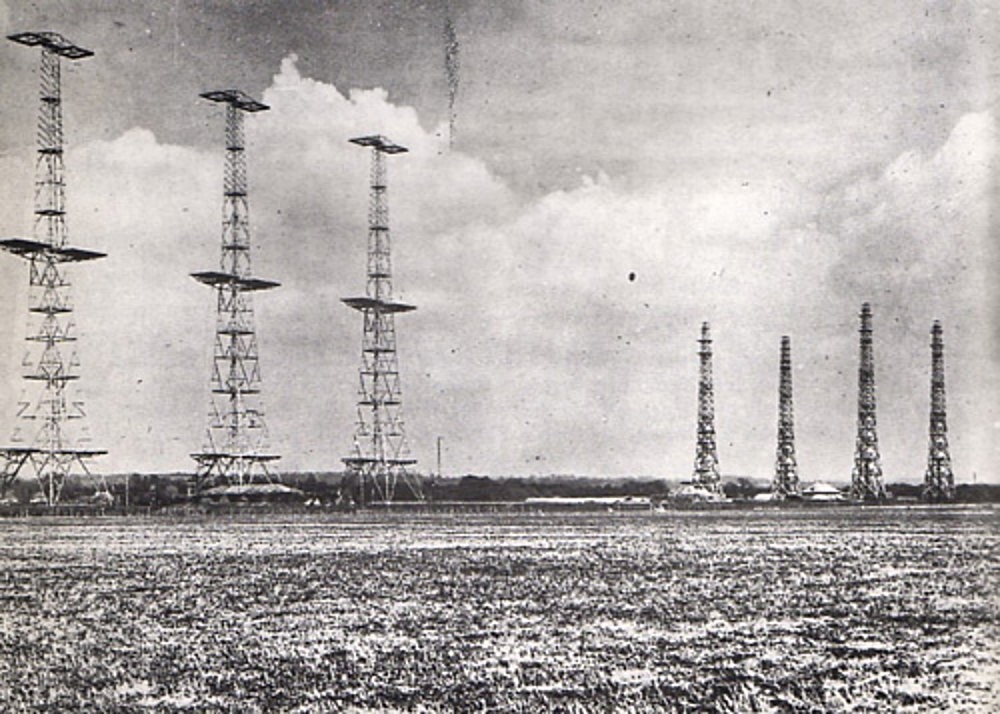

MANY who lived in West Sussex during World War Two were aware of the array of giant pylons at Poling, south of the A27 between Worthing and Arundel. They were large and prominent and their purpose was a secret that captured the imagination of local residents and attracted close scrutiny by the enemy.

The authorities were tight-lipped but did not discourage local rumours that the installation projected a death ray, capable of stopping the engines of enemy aircraft at a considerable distance. It was good propaganda (for us) and improved the morale of the local populace no end. In fact, those pylons at Poling were far more valuable to the war effort than a method of disabling the occasional passing enemy aircraft. There was another aspect of the Poling story that remained a top secret even after WW2 ended.

The Poling pylons were an integral part of Britain’s wartime early warning radar chain, without which we may never have won the Battle of Britain in 1940 or, indeed, World War Two.

While the Poling pylons were there for all to see (including enemy pilots) few apart from residents in the immediate area were aware that another much less obvious but closely related radar station had been built on top of Truleigh Hill, at the back of Shoreham. This also played a vital role in the chain of radar detector stations hurriedly thrown around Britain at the outbreak of WW2 in 1939.

Many are aware that years after the war, a BBC TV repeater transmitter and aerial was erected on Truleigh Hill to improve local reception of TV programmes. But of the wartime underground radar complex that had been built only yards away and was capable of withstanding the blast of a nuclear weapon, most people knew nothing at all.

The Poling radar pylons were erected before that at Truleigh Hill and from the beginning of World War Two formed an integral part of a chain of radar stations that ringed Britain to give early warning of approaching enemy aircraft.

They were part of the Chain Home (CH) radar system, capable of “seeing” targets approaching Britain, but not reliably if the enemy planes were flying low.

So Britain’s boffins developed CHL (or Chain Home Low) stations to provide essential low-level coverage down to 300 feet. Truleigh Hill was originally one of these.

The third stage of development introduced CHEL (Chain Home Extra Low) theoretically able to detect virtually anything that moved, though at shorter range. Truleigh Hill was converted to CHEL but not until 1952 and the Cold War.

Early in WW2 a German pilot could approach to within 80 miles of the British coast before the CH radar detected his plane. This was sufficient to give early warning of the majority of enemy aircraft as they approached our coast in large formations during the Battle of Britain, but in later and smaller bombing raids the German pilots soon realised that, by descending to below 5,000 feet they could evade detection to within 50 miles of the coast.

By 1941 we had the first CHL detectors in place but in the deadly cat-and-mouse game that ensued the enemy found they could evade detection by both CH and CHL radar by flying below 100 feet.

This led to a spate of hit-and-run raids on the South Coast that I remember only too vividly when individual German bombers suddenly appeared over the local coastline, dropped their bombs and made their getaway before our Spitfire or Hurricane fighters could intercept them.

This in turn led to the development of the CHEL system, with the ability to track aircraft up to 45 miles away and flying as low as 50 feet.

By this time many local residents knew that RAF personnel were manning what they believed was “a minor aircraft spotting outpost” on nearby Truleigh Hill, because many of the personnel were billeted in local private homes.

But what remained top secret for years was that, from 1939, Truleigh Hill was a vital link in Britain’s radar chain, closely connected with the major radar station at Poling.

From being one of the original CHL stations of WW2, Truleigh Hill was converted into a CHEL site in 1952 and continued as an important link in our radio defence system during the Cold War with Russia.

Few realise that even today, 40 feet beneath the prominent South Downs hilltop, remains a bunker and network of tunnels with walls of 10ft thick Ferro concrete, capable of withstanding a nearby nuclear blast – all evidence of its importance to Britain’s defence strategy in WW2 and the Cold War.

Today, all the tunnels are secured and impenetrable.

Early in WW2, Truleigh Hill was manned by a handful of RAF personnel. At its peak there were nearly 200. These are the men and women whose story Roy Taylor spent several years researching before producing his book, “Shoreham’s Radar Station – the true story of RAF Truleigh Hill.” Roy was himself in the RAF and stationed at Truleigh Hill during part of the Cold War period. He is able to relate, with first-hand knowledge, the fascinating story of how Shoreham’s highest hill played an intriguing – and vital – secret role in Britain’s air defences for more than a decade.