Smugglers at Worthing

IT was two o’clock in the morning of February 22nd 1832. A boat carrying more than 300 tubs of contraband spirits beached on the sand opposite Stafford’s Library on Worthing seafront. Despite the beach being bathed in bright moonlight, 200 men – a motley crowd of smugglers, their helpers and bodyguards – set about unloading an illegal cargo that included Dutch gin, French brandy and perfumes.

THE most notorious local smugglers `run’ ever was about to rudely awaken the inhabitants of Worthing from their peaceful slumbers. Before the first glimmer of dawn one man would be dead and many others wounded, following a running battle that was to mark the beginning of the end of what for centuries had been the lucrative Sussex smuggling `trade.’

In the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, times were tough. Negro slavery had only just been abolished, the Duke of Wellington was opposing the Reform Bill, many English farm labourers were starving and desperate and the trial of the Tolpuddle Martyrs had sent a shudder through the working population.

Hardly surprising that many of Worthing’s residents took advantage of their seaside location to benefit in some way from the smuggling trade. Some participated in the hope of quick profit. Others took part for the excitement or what they were pleased to refer to as sport.

During daylight hours, many of Worthing’s smugglers were legitimate fishermen, businessmen, craftsmen or farm labourers but during the hours of darkness they took part in contraband trafficking to boost their lowly incomes.

Many a schoolboy was allowed to sail on a smuggling run during school holidays and only regretted having to keep details of their adventure a dark secret from their best friends.

Despite efforts of the local Preventative Force and a Revenue cutter stationed at Worthing, there were frequent clashes between smugglers and the forces of law and order. They often ended in bloodshed.

The smugglers landed their cargoes of wine, spirits and tobacco quite openly, often aided by country people from villages like Tarring, Sompting and Steyning.

Local historian Edward Snewin recalled a few years later: `Most residents were generally on the side of the smuggler. Even the church did not frown on smuggling, though we should take with a grain of salt the tales of church services being postponed owing to the pulpit being crammed with smuggled tea or spirits.

`No doubt a certain amount of `brandy for the parson, baccy for the clerk’ found its way to Broadwater, where it was said a parish clerk used to signal to the smugglers by means of a flag on the church tower, but as the smuggling was usually done at night this story is held in some doubt.

But on Tuesday, February 22nd 1832, everything went badly wrong.

One regular routine for the smugglers was to meet up with their helpers near the Half Brick Inn at East Worthing. Farm horses would be walked out to the arriving vessel at low tide for the unloading then, in the early hours of the morning, the smugglers could expect to enjoy a straight run with their booty across the marshland then separating Worthing from Lancing.

Using several tracks running from north to south, they would maintain a low profile as they crossed Broadwater Brook and made for the Marquis of Granby inn at Sompting.

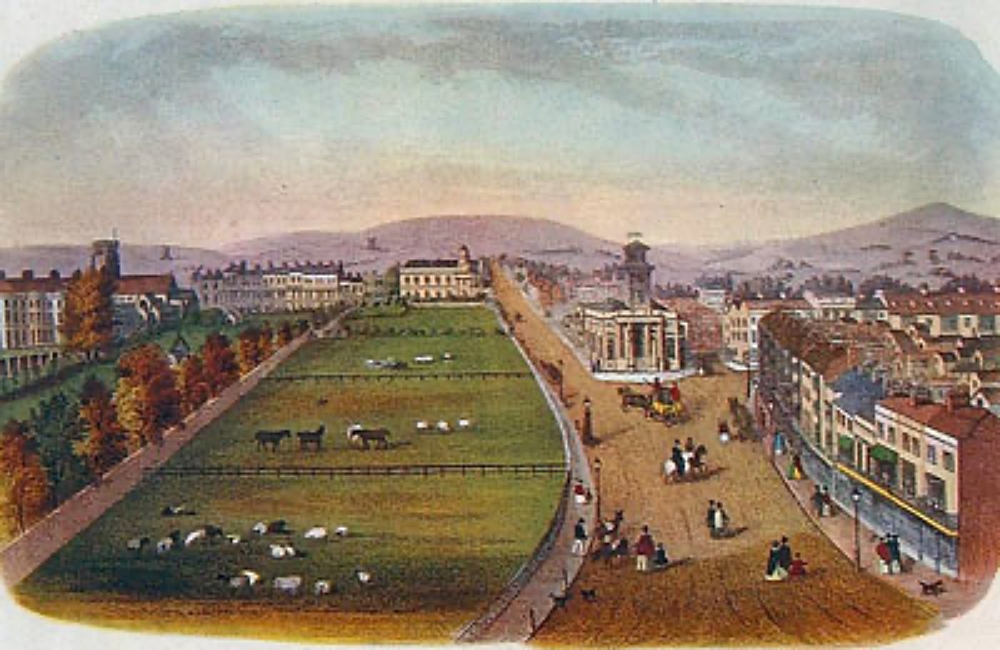

But the smugglers had become over-confident and on this occasion, for a reason never revealed, a last-minute decision was made to land a substantial shipment of contraband at a much riskier beach location, opposite Stafford’s Library between today’s Steyne Gardens and South Street. It would then be taken inland by a more westerly route.

The smugglers and their helpers – backed-up by a group of so-called batsmen for protection, some with heavy six-foot hazel staves others with firearms – began making their way slowly towards the High Street.

Customs officers had witnessed the landing but in the face of overwhelming odds could only summon assistance.

Aid was quickly forthcoming, suggesting they may have had prior knowledge of the `run. Each man as he appeared discharged his pistol, which sent notice along the coast for two miles east and west.

Raising the alarm in this way brought several mounted preventative officers.

But the smugglers were familiar with Worthing and made use of numerous narrow passages unknown to the coastguards.

In Warwick Street, some residents opened their doors to the smugglers who then escaped via the back doors into the next street. For a short time this baffled their pursuers who grew desperate. `For over an hour great uproar prevailed,’ reported a witness.

Cook’s Row

The mounted officers galloped too and fro firing their pistols but above even this noise could be heard the cheers of the majority of the smugglers and helpers as they made off with the kegs of brandy.

More than thirty minders brought up the rear managing to keep the customs officers at bay until they reached a footbridge crossing the Teville stream, not far from where today Broadwater Bridge spans the railway.

Among those protecting the smugglers was William Cowerson, a 31-year-old stonemason from Steyning, whose day job had been helping to repair West Tarring Church. `As fine a fellow and thorough Englishman as ever lived’ was how he was described by his fellow craftsmen.

But as the smugglers retreated with their booty towards the relative safety of the Downs, William Cowerson stayed to block the footbridge and confront Lieutenant Henderson, in charge of the pursuing force.

To disable his foe, the powerful Cowerson (reportedly uttering many oaths) struck the officers with so much force he broke his own arm. Then, using his uninjured hand the lieutenant, coolly raised his pistol and killed Cowerson with a single shot.

The coroner’s jury, at an inquest held in the nearby Anchor Inn, decided that the killing was justified.

Few of the smuggled kegs of brandy were ever recovered, having been quickly dispersed to numerous hiding places in Broadwater, Tarring, Sompting, Lancing, and Steyning.

Such had been the severity of the conflict that the authorities moved a troop of dragoons into Worthing. Quartered in the town for the next two years, they had such an inhibiting effect on smuggling that even the most the active participants give it up as too risky.

There is no doubt that the so-called Battle of Teville Footbridge marked the beginning of the end of big-time smuggling through Worthing.

From then on, only small parcels of smuggled goods were occasionally reported along the coast and by 1850 even that had come to an end.

For William Cowerson there was a hero’s burial in Steyning churchyard, with no hint in the epitaph on his gravestone that he lost his life while fighting against the lawful forces of his country. It reads:

`Death with his dart doth pierce my heart

When I was in my prime.

Grieve not for me my dearest friends

For it was God’s appointed time.

Our life hangs by a single thread

Which soon is cut and we are dead,

Therefore repent, make no delay,

For in my bloom I was called away.’

As for the landed gentry and rich farmers of the district who for so many years had enjoyed getting their favourite `Hollands’ (Dutch gin) and Boulogne Brandy on the cheap (or for nothing, in exchange for temporarily hiding the smugglers booty in their outhouses) relief came sooner than expected.

The government realised that reducing the swingeing tax on spirits might be the best way of finally ending the illegal and dangerous business – and so it proved to be.