Fever Year – 1893

THE 9.49 train rattled out of Worthing Station on the hot and windless June morning in 1893 and the other passengers, struggling with big suitcases, were too busy mopping their brows to take much notice of the man gripping a small wooden box.

Yet that man held the key to the most tragic period in the history of Worthing, in a box containing nothing but water in three small, carefully stoppered bottles marked A, B and C.

It was being taken to Edgar Crookshank, Professor of Bacteriology at King’s College, London. His report, made after carefully analysing the three bottles of apparently harmless clear water, was to rock Worthing to its municipal foundations.

Worthing, with a jealously guarded reputation as a health resort, was about to be described as “like a city of the dead.”

WORTHING had become a municipal borough only three years earlier. The town’s population had risen sharply from 12,000 to 17,000 in a single decade and the mayor, Alderman Edward Patching, was presiding over stormy meetings about Worthing’s future.

One allegation was that, due to the startling population increase, the town’s drainage was proving deficient.

Drought during the early summer of 1893 showed that the water supply was also inadequate, but here some action was being taken. By April, council workmen were digging deeply near Park Road, an area where an underground supply of fresh water was believed to exist.

As the workings probed towards Worthing Infirmary, water suddenly burst into the diggings, pouring in so rapidly that workmen had to run for their lives. It was also accompanied by an “abominable stench.”

Nineteen days later, two cases of typhoid fever were reported to Dr Charles Kelly, Worthing’s medical officer of health. A further 60 further cases were reported during the second week of May and the worst fears were confirmed the following week when 42 cases were ed in one day.

Everybody was alerted to boil all drinking water.

Dr Edgar Crookshank, at King’s College, London, received the first water samples from Worthing on Friday of Whit weekend. He left them untouched in his laboratory until Tuesday morning.

In the report on his analysis to the mayor of Worthing several days later, the professor stated, “The number of bacteria in the water is far too high. It contains more bacteria than unfiltered Thames water in December.”

But the mayor did not even show the report to the town council’s sanitary committee. With the medical officer, Dr Charles Kelly, he decided, “because the samples have been left for more than three days before the analysis was done it cannot be accepted as a reliable condition of the water.”

Crookshank agreed to carry out an analysis on a second batch of samples and it was these bottles, marked A, B and C, that were taken to London by Dr Kelly. In his subsequent report, Crookshank stated, “They contain bacteriologically pure water, standing in marked contrast to the first samples which gave unquestionable evidence of contamination by filth.”

The mayor was pleased. He published this reassuring second report on the day it was received at the town hall. Contents of the earlier report remained secret, though by this time its existence had been revealed.

By June 9, 248 cases of typhoid had been reported in the town and 30 people had died of the disease, but so few cases were reported the following week – by now everybody was boiling drinking water and milk – that on June 16 the mayor and town clerk, the medical officer and the chairman of the sanitary committee all signed a statement declaring, “The epidemic may be considered at an end.”

It proved a fatal misjudgement of massive proportions.

Reassured by the official statement, many people were no longer boiling their water. Between July 1 and 19, the dreaded disease struck 548 people in the town.

A special week of prayer was called for. Those who could afford to moved away from Worthing. Many pretty villas were shuttered up and gates were padlocked.

Large, fashionable and expensive homes went up for sale at prices that were to drop even lower as the fever took its course. The houses were advertised for sale week after week, not a buyer in sight.

It was to become local legend, probably with a basis of truth though never proven, that this situation led to a conspiracy between local men who were nicknamed “Worthing’s Forty Thieves”.

Were they members of the town council, ambitious local businessmen – or both? The belief remains that many of the so-called “Forty Thieves” became wealthy because they purchased property at rock bottom fever year prices and re-sold them later at vast profits.

Meanwhile, the typhoid persisted. By mid-July, nurses had been called in from London, church halls commandeered as temporary hospitals and two large hospital tents erected in the grounds of Worthing Infirmary to help accommodate the overflow of victims.

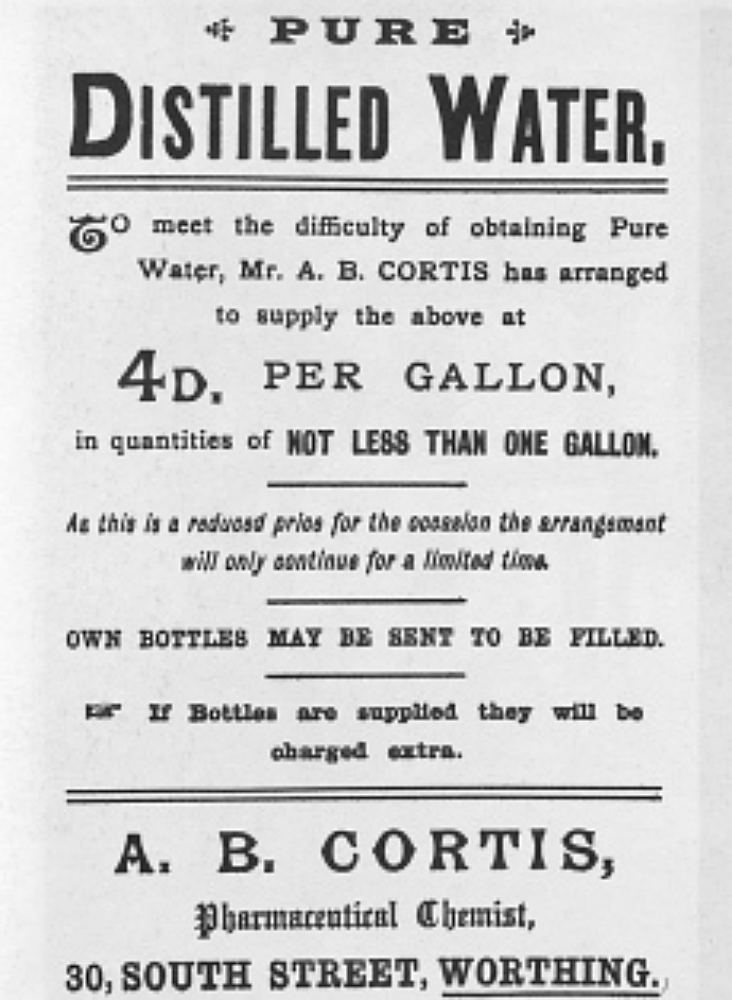

Galvanised 100-gallon tanks were set up in the main streets of Worthing and from these, maid servants, men with bottles and jugs boys and girls with tin cans, took home essential supplied of fresh, pure drinking water.

This was being brought by horse-drawn water carts from the independent West Worthing Water Works (adjacent to the public baths then in Heene Road) and Shoreham Water Works.

It was noted in the Worthing Gazette at the time, “Three-fifths of victims are women and children and the proportion of deaths is higher among the well-to-do class.”

And still the tragedy was not at an end. During July alone, 678 more cases were reported.

Not until the end of that month was the source of the epidemic finally admitted to be the impure new water supply “fed by a watercourse under fields hitherto used by the municipal authorities as a sewage farm.”

By mid-August you could walk through the main streets of Worthing and probably see only two vehicles and one of those would be a hearse.

Meanwhile, Alderman Cortis, who had been Worthing’s first mayor, was personally sponsoring boring experiments at Sompting to find a fresh water supply.

The breakthrough finally came on August 22, when a plentiful supply of good, clean fresh water was discovered. Within days the engines of Worthing’s polluted town centre waterworks were stopped forever.

Rows over who was to blame for the tragedy that claimed so many Worthing lives went on for years, while official sources appeared to take comfort in stressing that “the percentage of deaths in the Worthing epidemic did not approach the “ordinary” rate in similar outbreaks elsewhere.”

More than a century later, the observation seems an unworthy summation of Worthing’s greatest town-wide tragedy in which nobody but the victims paid the price for the most appalling public blunder in local history.

If such a catalogue of errors were perpetrated today the resulting lawsuits would probably send both the town council and the local health authority into bankruptcy.