The Longest Day

IT took three years to plan what top generals and politicians knew in secret as “Operation Overlord”. By the time it was launched early in the morning of June 6, 1944, everybody knew it as “D-Day” and southern England had become the springboard for the biggest unified armed invasion the world had ever seen.

TWO million troops with 365,000 tanks and other military vehicles were assembled in the south of England in the build-up to D-Day.

During the first four months of 1944, the area had become one vast military camp, cordoned off from the rest of Britain by a line drawn on the map that no unauthorised person was allowed to cross in either direction.

Worthing had the first hint of momentous events to come when the 4th Armoured Brigade – veterans of the famous 8th Army that had defeated the Germans and Italians in the North African campaign – arrived in the town on February 10, 1944.

They brought with them 200 tanks, set up headquarters in the Eardley House Hotel on Marine Parade and settled into billets in the Steyne and surrounding roads.

When the large Goring mansion called Courtlands was taken over as headquarters for the Canadian 1st Army, it was evident that “something major” was in the offing. Could this possibly be the long hoped-for “Second Front”, the invasion of the Nazi-occupied European mainland that everybody on this side of the Channel – and the hard-pressed Russians in the east –- had been hoping for since 1942?

If further evidence was needed that matters of the greatest importance were stirring, it was the arrival of British Commando units who promptly established headquarters at Broadwater Road, Worthing.

Suddenly, the woods around Castle Goring on the Arundel Road seemed to come alive with armoured vehicles using trees as the ultimate form of camouflage.

By the end of February, the United States 30th Infantry Division was undergoing intensive training in the Arundel area, vast tracts of countryside encompassing Angmering, Patching, Burpham and Clapham having been requisitioned by the War Office for this purpose.

The previous September, a highly secret British army detachment had discreetly set up base at a house in Littlehampton. To the few who knew of its existence, this was X Troop of No 10 Inter-Allied Commando, largely recruited from armed services exiles that had escaped from Nazi-occupied countries in Europe.

Never destined to fight as a single unit, members of X Troop played invaluable roles as individuals in the build-up to D-Day, taking part in invaluable, highly dangerous, under-cover reconnaissance raids on the German-occupied French coast.

By this time, troops pouring into this area of West Sussex resembled a roll-call of the British Army’s most famous units. The 15th Scottish Division had made Worthing’s seafront Beach Hotel its HQ and dispersed its artillery between Worthing, Lancing and Ashington.

The 2nd Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders moved into a tented camp at Cissbury, the 2nd Gordon Highlanders created a similar one at Muntham Court near Findon while the 10th Highland Light Infantry occupied Wiston House and its grounds near Steyning.

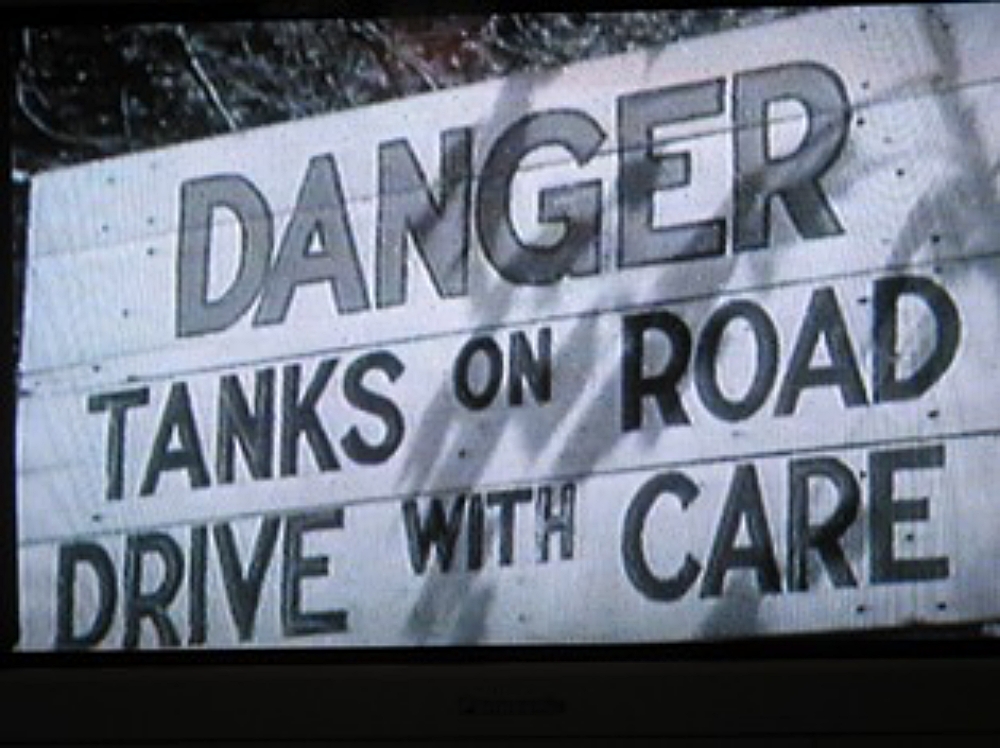

Gunfire and the screech and clatter of tank tracks became familiar sounds in surrounding country villages, including Storrington.

Hilltops and farms, once isolated havens of peace and tranquillity, were pounded day and night by all types of artillery and small arms as training gained intensity.

Prime minister Winston Churchill and Allied Supreme Commander General Eisenhower visited the area to watch the training. Contingency plans were made in Worthing in anticipation of heavy casualties on D-Day.

A large field near Southways Avenue and West Street, Sompting, was laid out with huts and tents to receive wounded allied troops and captured Germans.

As D-Day drew closer, aircraft of a long-range Mustang squadron based at Ford penetrated deeply into Europe on “spy in the sky” reconnaissance missions. One of them flew from Ford almost to the Swiss border and back!

Ian Thomson, of Ferring, was then a young lad living with his family at Goring. He recalls those exciting days during the build-up to D-Day in May and June, 1944.

“Alinora Crescent was lined on both sides with Bren Gun carriers,” he remembered, “and what is today a pleasant area of grass between George V Avenue and Wallace Avenue was then a military vehicle park overflowing with Jeeps.

“At the eastern end of Marine Crescent, where the Anchor Court flats are today, soldiers excavated a deep pit with graduated sides, which they concreted and filled with water. Then, having waterproofed the engines of their three-ton and 15cwt vehicles, they had to run them into the water and out the other side to test the effectiveness of their work.

“No doubt it was invaluable preparation for the D-Day landings from the sea but you should have heard the jeers from other army drivers when the occasional failure gurgled to a standstill and had to be towed out of the deep end!”

He also remembers light tanks being jam-packed into Latimer Road and heavier Churchill tanks lining the entire length of Wallace Avenue. Even so, the bus which took him to school managed to squeeze through quite easily, though many pavements and kerbs were damaged in the process.

Suddenly, at 01.00 hours on Saturday, May 26, all the army camps in the area were sealed off and troops “virtually vanished” from the outside world. Such was the need for total secrecy at this critical time that all except the highest priority military communication was forbidden, both into and out of the area.

By May 28, the roads of Sussex were thronged with long columns of military vehicles on the move.

In Worthing, where, during the previous six months, the sights and sounds of thousands of troops and their armoured vehicles had become so familiar, residents were surprised to suddenly find silent, empty streets and green empty spaces.

After days agonising over the weather forecast, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe, announced … “OK, we’ll go”.

Setting sail from the south coast of England the night before, to arrive off the German occupied French Normandy coast on D-Day, Wednesday, June 6, 1944, the troops filled 1,000 warships, 1,200 merchant ships and 4,200 landing craft.

I vividly remember being awakened just after 5am on June 6, 1944, by an unfamiliar sound.

gradually lighting sky above Worthing was grey with aircraft heading out to sea, a scene unrivalled even in the darkest days of the Battle of Britain.

It was, of course, only the beginning of the end of the war in Europe. Almost another year of intense struggle on land, sea and air had to be endured before the German forces finally surrendered unconditionally at 2.41am on Monday, May 7, 1945.