Worthing to the West

TODAY, some of the most prestigious properties in town grace the western half of Worthing where it is closest to the sea. But the area did not always enjoy its present up-market cachet. During the 18th and early 19th centuries it had an appalling reputation, which stemmed from the amount of surplus water that lay on the land south of what today is Richmond Road and Mill Road. This meant that for much of each year the area was turned into a virtual swampland, before the water was eventually carried down to the sea through a network of ditches.

As the town grew, these ditches also served as drains and carried sewage and surface water indiscriminately, depositing it all on the beach for the tide to clear away.

The situation only worsened when the stream believed to be the cause of these waterlogged areas began to dry up. The ditches became choked with an accumulation of rubbish that had been thrown into them.

Not surprisingly, the result was a source of endless trouble and offensiveness for local authorities, residents and visitors alike. It is not difficult to imagine why the situation held back the development of the south-west part of Worthing for many years.

Another inhibiting problem for 18th and early 19th Worthing was a broad stretch of pastureland known as Worthing Common, or Salt Grass. This lay south of the swampy land and stretched westwards from approximately where the Pier is located today. Its only buildings were a couple of small houses and an inn.

The problem here was that the fine clay used for making the light cream bricks preferred by Worthing’s early property developers was dug from this very Common.

Unfortunately, the policy of allowing this to happen, combined with the extensive removal of seashore shingle for road making during the early part of the 19th century, accelerated sea erosion to a dangerous level. Nearly 300 yards of Worthing’s southern boundary land was washed away in the century before Worthing’s first sea defence works were undertaken in 1821.

In the late 18th century, Worthing had been a mere one-street community, with an approach from the more substantial village of Broadwater at that time by way of South Farm Road, then called Brookstead Lane.

The single street of the tiny town itself was called Worthing Street (which we now know as High Street) and this meandered towards the sea. Apart from an isolated farmhouse or two, all the main buildings were located in Worthing Street.

Warwick Street, South Street, Cross Lane (later Montague Street) and East Lane (which later became Brighton Road) were only farm tracks. Another track followed an embankment along the present seafront to Heene.

But by the 1820s the village had blossomed into a small town, even having its own purpose-built theatre.

Building the seafront Esplanade as far as West Buildings began in 1819; before that the sea often overflowed across the rough seafront track and into the houses beyond. The gesture was sufficient to encourage Worthing’s spread westwards, though raising the promenade to the relatively high level we know today did not follow until the 1860s.

Worthingquo&rs;s Victorian historian, Edward Snewin, who left much of this detail in his contemporary notes, informs us that Montague Place was built between 1802 and 1805; that the Royal Baths (later called Marlborough House) was built around 1824 at a cost of nearly £6,000; and that Paragon Street was created at around the same time as the Baths – adding as a footnote that in those days there were no bye-laws to prevent people building just as they liked.

At this time, the last houses in Worthing, before the open space dividing the township from the village of Heene, were in West Terrace, at the sea end of West Buildings, The latter had been built by a man name Cranston and was originally named John Street.

West Buildings applied only to the houses on the west side of the road, the local authorities in those days often causing confusion by giving one name to a street and another to the buildings in it.

The Coastguard Station was the final building in the west Worthing of those days, butting right up to the boundary of Heene village. Close by there was a sand pit, used by the parish to give employment to the poor during the winter.

Next came two fields called Great Heene and Little Heene. The latter is now Brunswick Road. In 1801 there were only 16 houses in the whole of Heene but in the following 40 years the number rose to 184.

It was in 1865 that local government was invested in the West Worthing Improvement Commissioners, who proceeded to develop the district as a residential suburb of Worthing as the old name Heene gradually fell into disuse.

Back in the main part of Worthing, West Street consisted of small houses inhabited by fishermen and here was situated the Rambler Inn, one of the oldest licensed houses of the town.

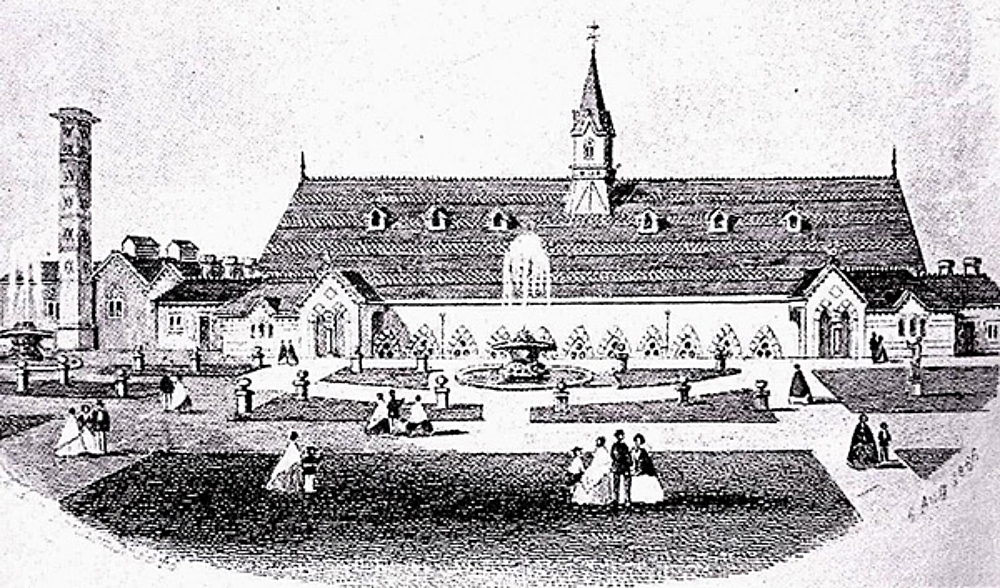

Development of Worthing into the largest town in West Sussex was only just beginning but interesting ideas were already being offered in efforts to attract new residents. An example was the scheme put forward by John James Esq, `the public-spirited proprietor of Liverpool Place.’

Edward Snewin recalled that in 1835 `John James erected a splendid gothic rural bower in a field adjoining Liverpool Place, intending to lay out a field as a bowling green, archery ground, etc., for the accommodation of visitors. The whole will be completed forthwith at a very considerable outlay, under the superintendence of Mr Ward, builder of the town.’

Edward Snewin also remembered Ambrose Place being built between 1814 and 1826 by Ambrose Cartwright, a local builder who died in 1845 at the age of 89. Even then Snewin referred to it as `one of the most delightful residential districts of Worthing, being situated on the high central ridge and having a clear view across open fields to the sea, and northward to the wooded grounds of Offington and Broadwater and the Downs beyond.’

That delightful impression is worth savouring. It perfectly sums up what must have been one of the best times in Worthing’s development, especially when much of the what followed in Victorian Worthing was dominated by riots, the reading of the Riot Act from the Town Hall steps, a disastrous fever outbreak caused by polluted drains and leading to many deaths, and a recession that nearly made the town bankrupt.

But we don’t want to spoil Edward Snewin’s happier memories.