Alfred Heublein – The Man Who Fell to Earth

WHEN Alfred Heublein dropped in on Mrs Phyllis Hansford one dark Saturday evening at the height of World War Two it was hardly a social visit.

To Mrs Hansford’s dismay her uninvited visitor literally dropped out of the sky, bounced off the roof of her house in First Avenue, Lancing, broke a tile or two and landed on a pile of coal in the back garden. Sixty-seven years later, Freddie Feest recalls the first, unexpected, experience some residents of Lancing gained of the German enemy.

UNTIL young Alfred Heublein’s startling arrival, the residents of First Avenue, Lancing, were convinced, like most people living in Britain in 1941, that all German’s wore coal scuttle helmets, looked like the devil incarnate and were quite capable of eating little children.

The arrival of young, good-looking and mild-mannered Alfred on that May weekend in ’41 dented their beliefs.

They knew the visitor was no angel from heaven because, even in the wartime blackout, it was evident, from the yards and yards of silk draped over the garden fence of Number 140, that Alfred had arrived by parachute.

Although wounded, the uninvited parachutist managed to struggle free from his harness and crawl down the back garden to a gate, where he collapsed.

Later, Phyllis Hansford told how, with her husband on duty with the Volunteer Fire Service, she was alone in the house.

“I heard a strange noise and looked out into the back garden. There I could see the enormous folds of a parachute hanging over several garden fences and became extremely nervous. Then I spotted an airman who was hurt and could only crawl. He was a fair-haired young man, no more than a boy really. My neighbours quickly brought him blankets and we gave him a drink of water as he lay at the end of the garden, moaning.”

By this time it was evident that the uninvited “visitor” was a German airman, a survivor from a raiding bomber that had been shot down by Allied fighters.

Another eyewitness told how she heard “a burst of machinegun fire, followed by a crashing noise.”

Four Red Cross nursing orderlies, on duty with the Civil Defence at their nearby Lancing Manor headquarters, were quickly on the scene.

One of them, a Mr Judge, was first to reach the parachutist. He described the airman as “suffering from cuts.” In fact, there were bullets lodged in his legs and thighs. “I thought at the time he had probably fallen on a glass conservatory,” said Mr Judge. “Certainly he had only just missed some high tension cables in First Avenue. “I went to loosen the clothing around his neck but the German believed I was going to strangle him. He could not be pacified until I pulled out my Red Cross badge, after which he calmed down a little.”

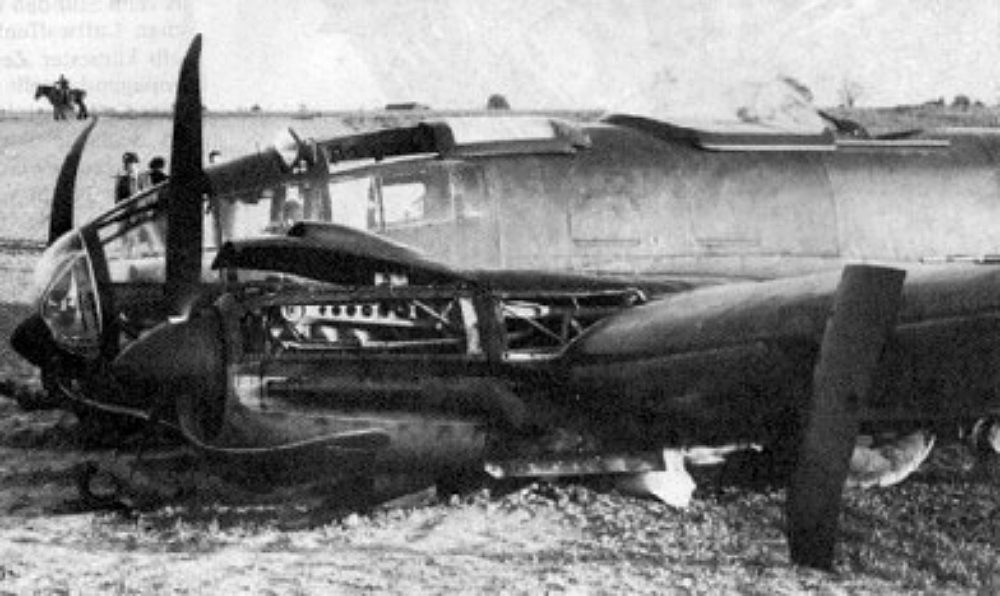

Mrs Hansford and her neighbours comforted the injured airman until an ambulance arrived and took him to Worthing Hospital – but that is not the end of the story. A search was launched for Alfred’s crashed Heinkel 111 aircraft and the rest of his crew. The plane was soon found. It had flown on for several miles before crashing shortly before midnight at Eastergate, to the west of Barnham Station. There, boot repairer, Frank Timlick, watched the blazing plane gliding with both engines out of action. He thought the machine was going to strike the roof of his house but it just maintained sufficient height to drift towards an old gravel pit near Eastergate Lane before belly flopping into the loose earth.

Geoffrey Binden, who lived nearby, said the plane approached his house in flames with pieces falling to the ground. It just missed his house and struck the gravel pit.

“When I ran to the plane I could see that it had broken its back. There were little fires all over the place and I helped the rescue services remove 200 incendiary bombs from the area. Other items recovered from the plane included a short-handled paddle ready for any emergency over the open sea and a rather pathetic looking teddy bear mascot which must have hung in the cockpit.”

After the end of the war, it was learned that the five-strong crew consisted of the pilot, Helmut Lees, observer Rafael Lekscha, wireless operator Ernst Gerlock, mechanic Herbert Dieterle and Alfred Heublein, the man who fell into the Lancing garden, who was the gunner.

The body of the pilot was never found, leading to the strong possibility that he bailed out over the Channel. Observer Lekscha jumped from the plane but died during his descent. He was buried at St James the Less Church, North Lancing, before being re-interred in the German section of Cannock Military Cemetery.

Another to die as he jumped from the aircraft was Herbert Dieterle, whose body was found beside his burned-out parachute on the Downs beside Cissbury Ring.

Mick Ockenden, of Nepcote, Findon, helped carry Herbert’s body down to the village on a sheep hurdle. The German airman was buried at Findon Parish Church until the mid-1960s, when his body was also removed to Cannock Military Cemetery. There remained only Ernest Gerlock, wireless operator, who, according to German records, was taken prisoner-of-war.

Meanwhile, at Worthing Hospital, Alfred Heublein was treated for a fractured femur and bullet wounds before being taken into custody. He remained a prisoner for the rest of the war.

On the same night that Albert Heublein landed in a Lancing garden, another German airman fell from the sky over Littlehampton. He managed to free himself from the blazing cockpit when an RAF fighter brought down his plane but his parachute failed to open.

As he dropped through the air one of his boots fell off and his watch fell out of his pocket. The boot landed in one street, the watch was picked up in another and the tail of his plane was found in the middle of a third road.

He was buried quietly in the local cemetery early the following Wednesday morning.